The Batavia’s Journey

The Batavia left Holland on her maiden voyage to the East Indies for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) with over 300 people on board, including civilians and minus a few desertions.

Experienced merchant Francisco Pelsaert commanded the Batavia. The main cargo included:

- Silver coins

- Two antiquities belonging to the artist Rubens for sale to an Indian Mogul ruler

- Pre-fabricated sandstone blocks for a portico

The original fleet of seven ships was separated soon after departure due to a violent storm. The Batavia found herself sailing in a fleet of just 3 ships, but despite the rocky start, the journey progressed well to the Cape of Good Hope.

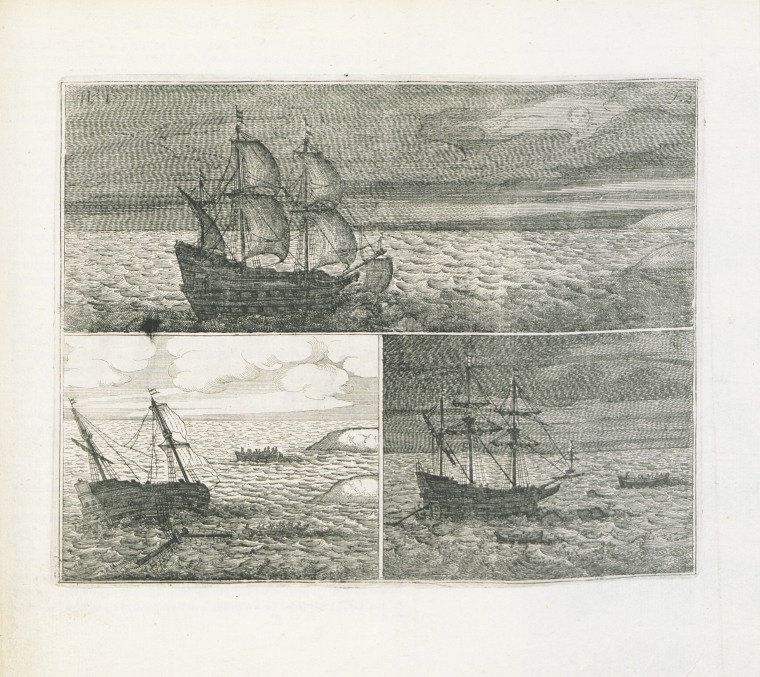

A Dutch East Indiaman.

A Dutch East Indiaman.

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b4642755_1

It was here that the troubles began for the crew of the Batavia.

Trouble Brews

Shortly after leaving Cape Town, three ships became one as the Batavia lost sight of the Assendelft and the Buren. During the Indian Ocean crossing, Pelsaert fell ill and spent much of his time in his cabin, unawares that discipline aboard the ship had begun to break down. Whether by design or accident, the Batavia ran aground on Morning Reef (Houtman Abrolohos, off the coast of Western Australia) on June 4th 1629.

As recorded in Pelsaert’s Journal:

‘FOURTH of JUNE, being Monday morning, on the 2 day of Whitsuntide, with a clear full moon about 2 hours before daybreak during the watch of the skipper (Ariaen Jacobsz), I was lying in my bunk feeling ill and felt suddenly, with a rough terrible movement, the bumping of the ship's rudder, and immediately after that I felt the ship held up in her course against the rocks, so that I fell out of my bunk. Whereon I ran up and discovered that all the sails were in Top, the wind South west, that during the night the course had been north east by North, and that lay right in the middle of a thick spray. Round the ship there was only a little surf, but shortly after that heard the Sea breaking hard round about. I said, "Skipper, what have you done that through your reckless carelessness you have run this noose round our necks?”’

The Batavia became the first Dutch ship lost off the coast of Western Australia, but further tragedy was to follow.

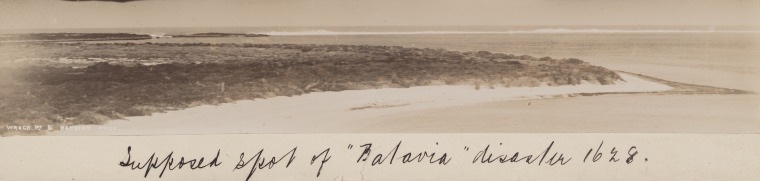

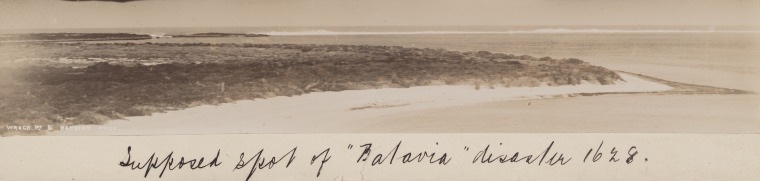

Supposed spot of Batavia disaster, 1628.

Supposed spot of Batavia disaster, 1628.

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b4724441_1

Water Worries

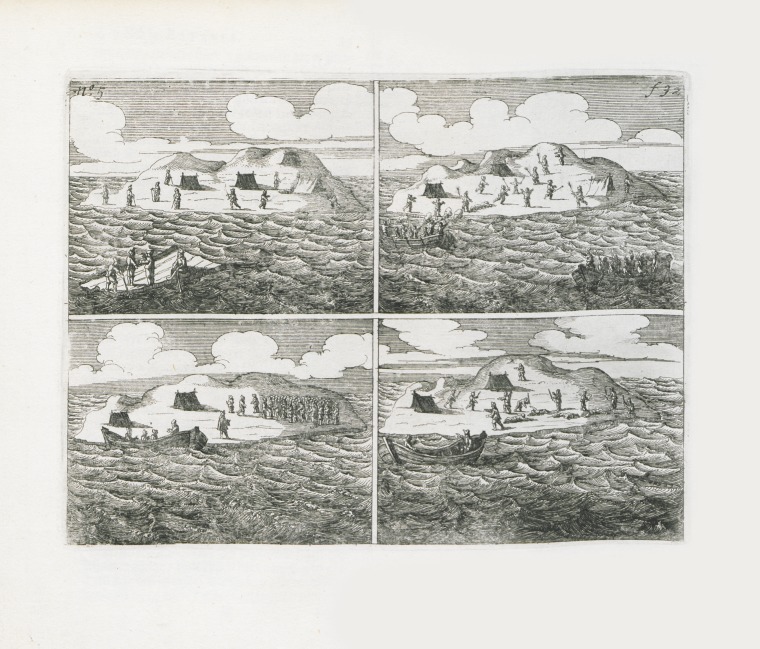

After the wrecking, 180 people were ferried off the ship, and around 70 remained onboard, including Jeronimus Cornelisz, the undermerchant.

Those who left the ship landed on Beacon Island, and approximately 40 men, including Pelsaert and Captain Jacobsz, made camp on Traitor’s Island with various supplies and provisions salvaged from the wreck.

The absence of fresh water would soon become an issue, as Pelsaert describes in his journal:

‘At last, after having discussed it very well and weighed up that there was no hope of getting water out of the ship unless the ship should fall to pieces and it [water in barrels] should so float to land, or that there should be a good daily rain with which we could quench our thirst (but as these were all very uncertain means), resolved after long debating, as appears out of the resolution, that we should go in search of water on the islands most nearby or on the continent [vaste landt] to keep them and us alive, and if we could find no water, that we should then sail with the boat without delay to Batavia, with God's grace there to relate our sad, unheard of, disastrous happening.’

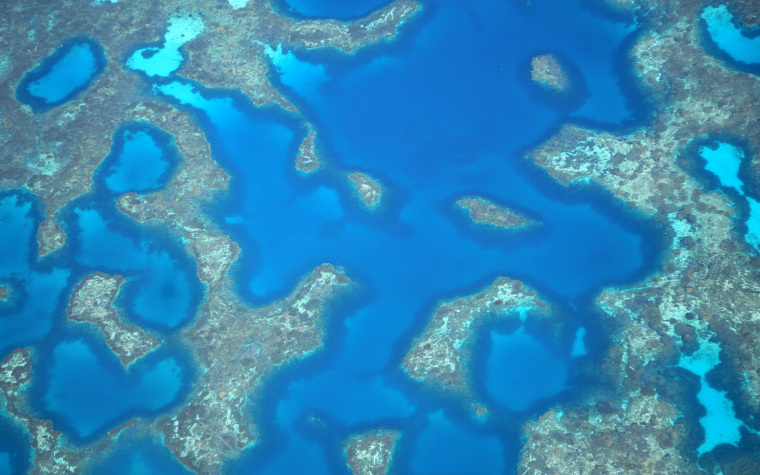

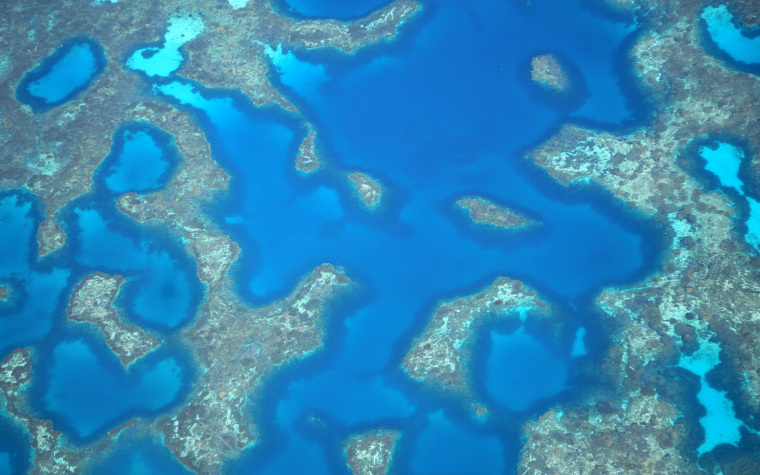

Aerial photographs of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands

Aerial photographs of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3024373_14

Aerial photographs of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands

Aerial photographs of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3024373_17

The Mutiny

Upon finding no water source nearby, all senior officers (excluding Cornelisz, still aboard ship), some crew and passengers (48 people in total), went in search of water on the mainland. When this proved fruitless, they began the journey to Batavia (capital of the Dutch East Indies) to find help – a journey which took them 33 days.

When this small group of people arrived in Batavia, the Batavia’s high boatswain was executed upon Pelsaert’s indictment, and the skipper Jacobsz was arrested for negligence, again on Pelsaert’s word. Seven days later, Pelsaert was sent to rescue shipwreck survivors in the jacht Sardam.

It took the Sardam a further 63 days to find the wreck site. Pelsaert was absent from the survivors of the Batavia shipwreck for over 100 days in total.

During the time of Pelsaert’s absence, the Batavia broke apart, drowning 40 men. Those who survived, including Cornelisz, made it to Beacon and Traitor islands.

Pelsaert’s quick departure left Batavia’s survivors bitter and distressed. Cornelisz took advantage of this perilous atmosphere, asserting himself as a leader of a band of approximately 40 men, with the intention to capture any relief ship that might come for the survivors and take off with it.

To eliminate opposition, he systematically went about cutting out the remaining survivors by any means possible. Methods of elimination included dehydration, erroneous expeditions on the mainland, drowning, and outright murder of men, women (some were kept alive for obvious reasons), and children alike.

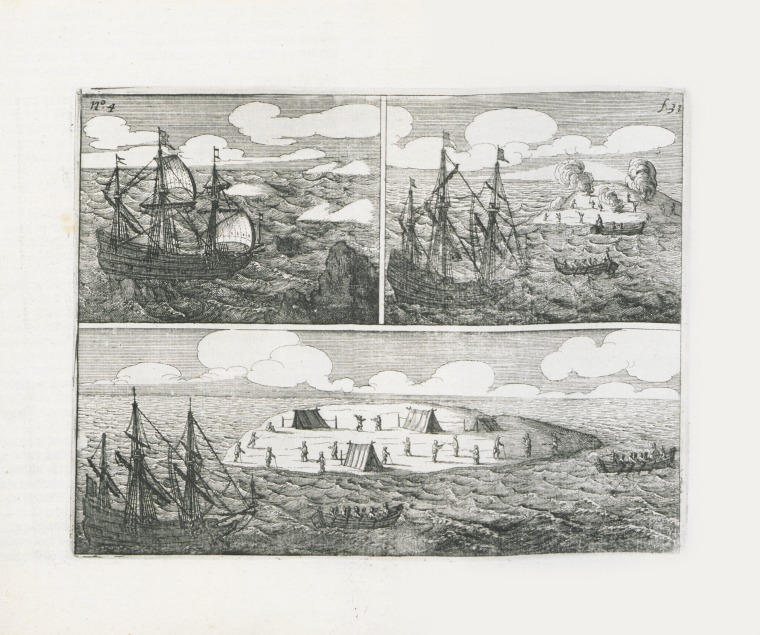

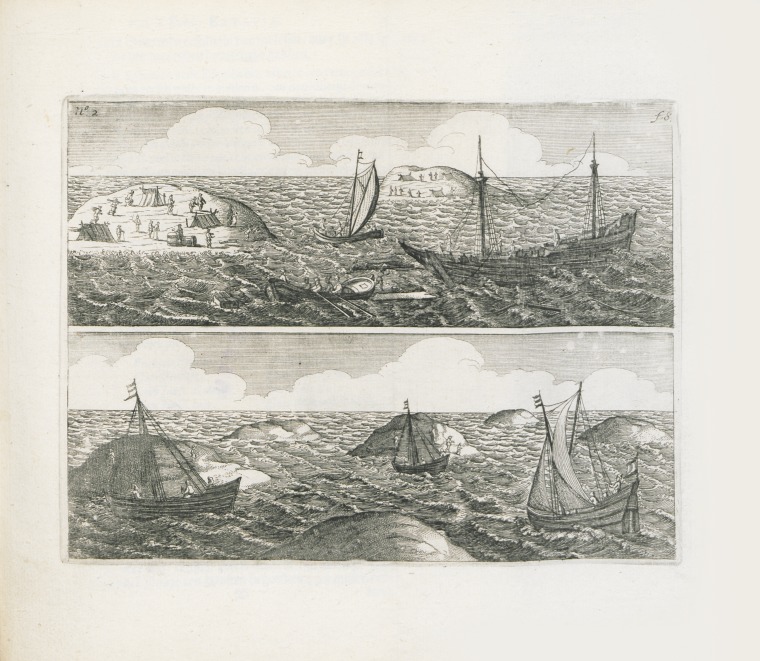

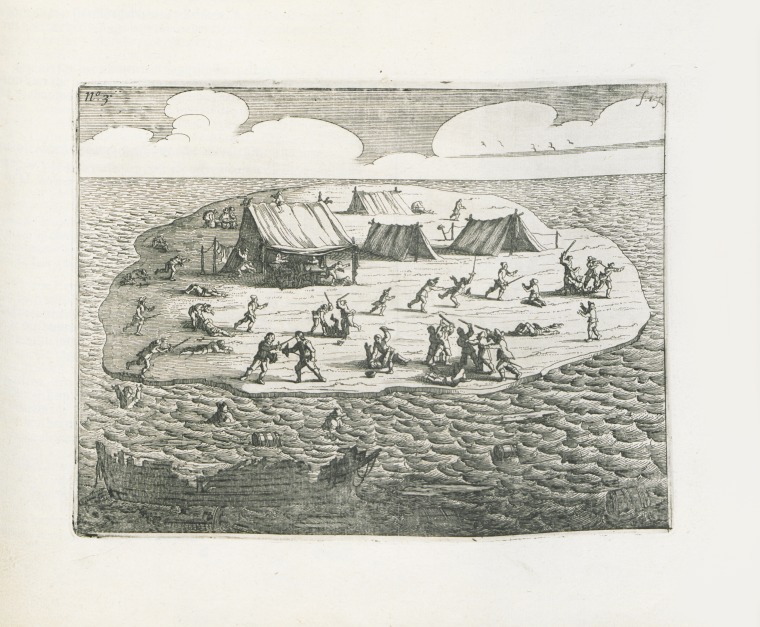

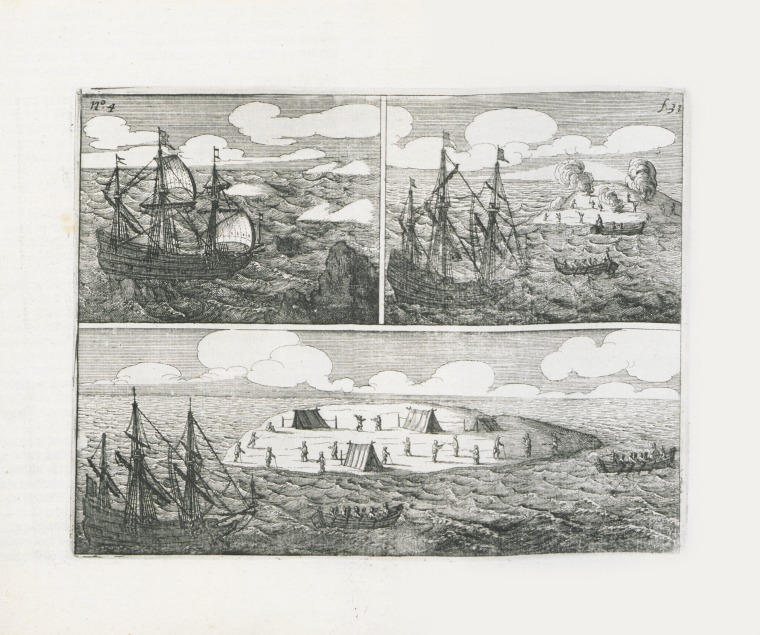

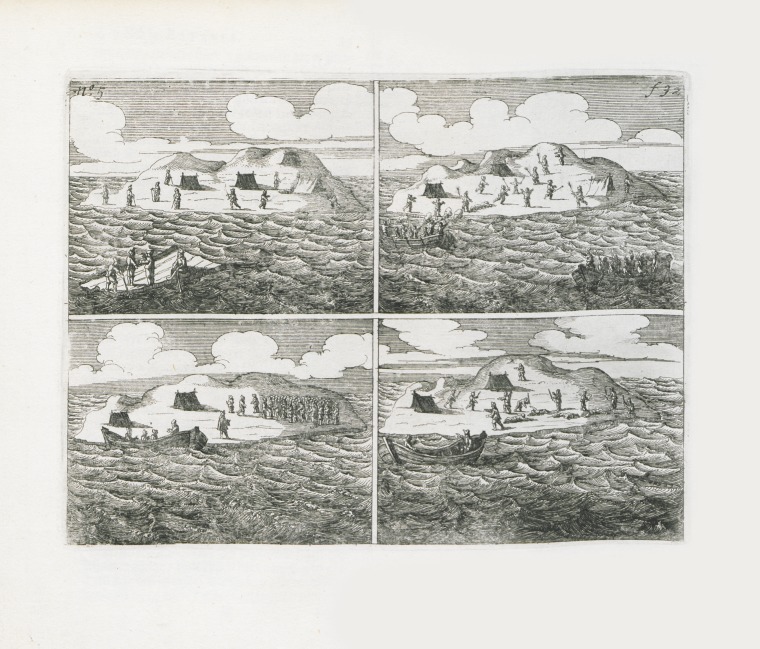

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_4

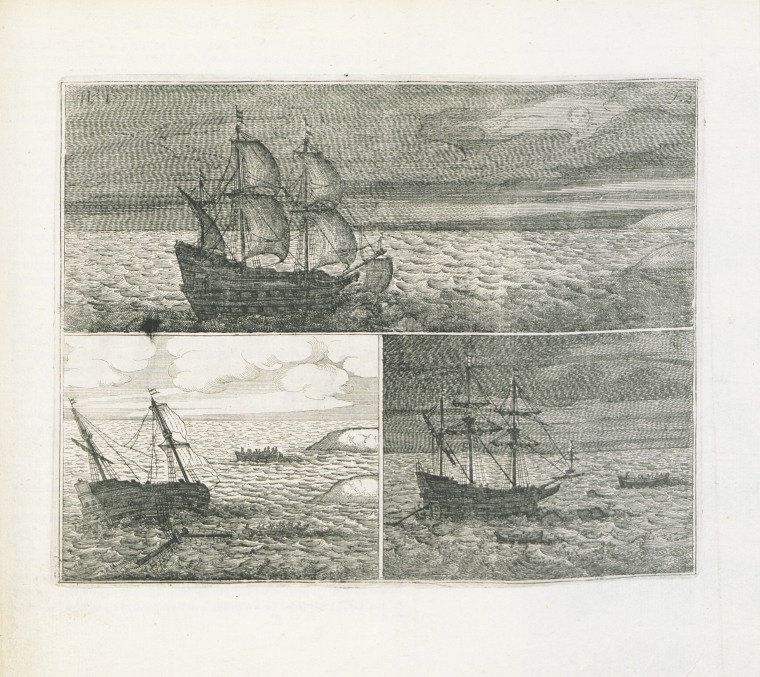

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_2

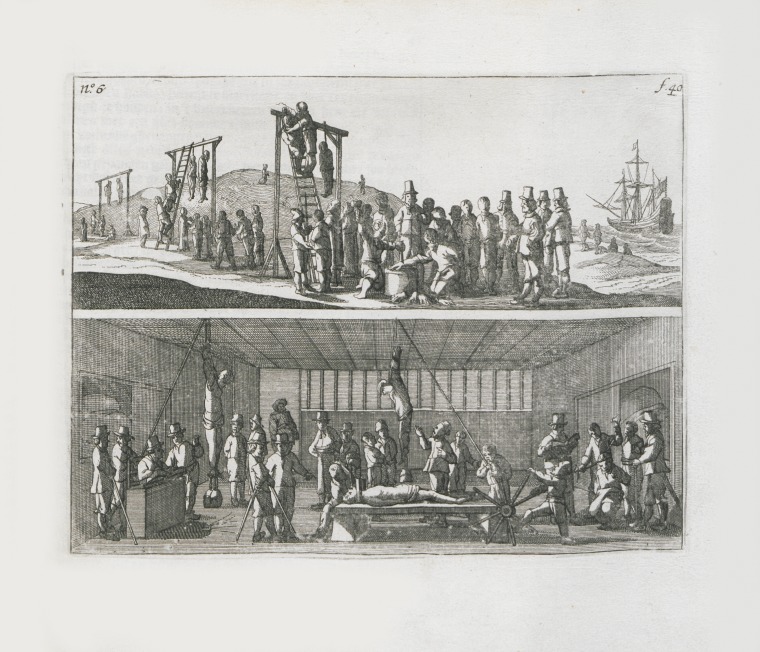

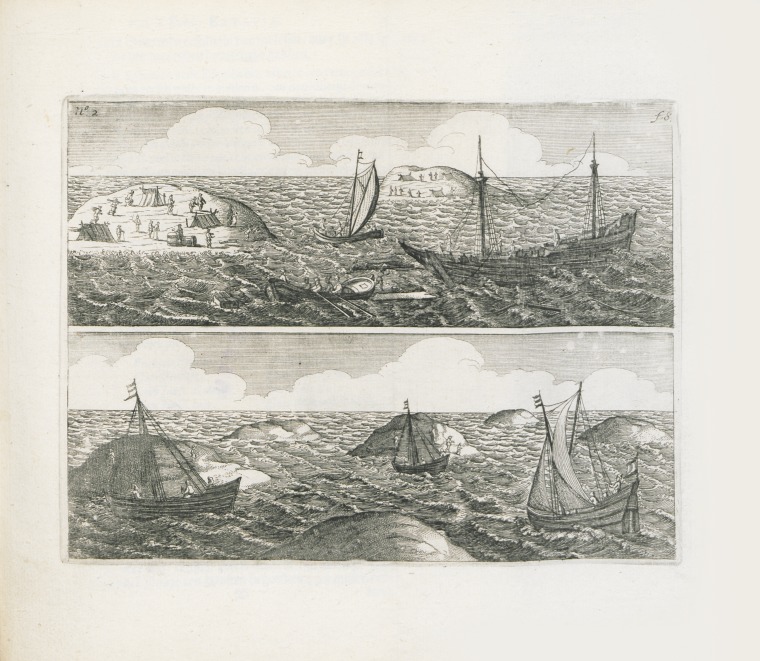

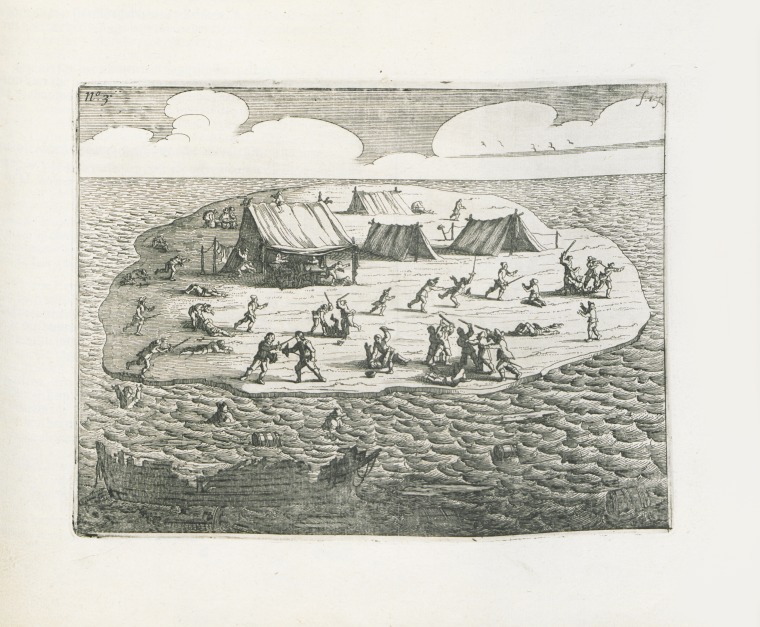

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_6

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_1

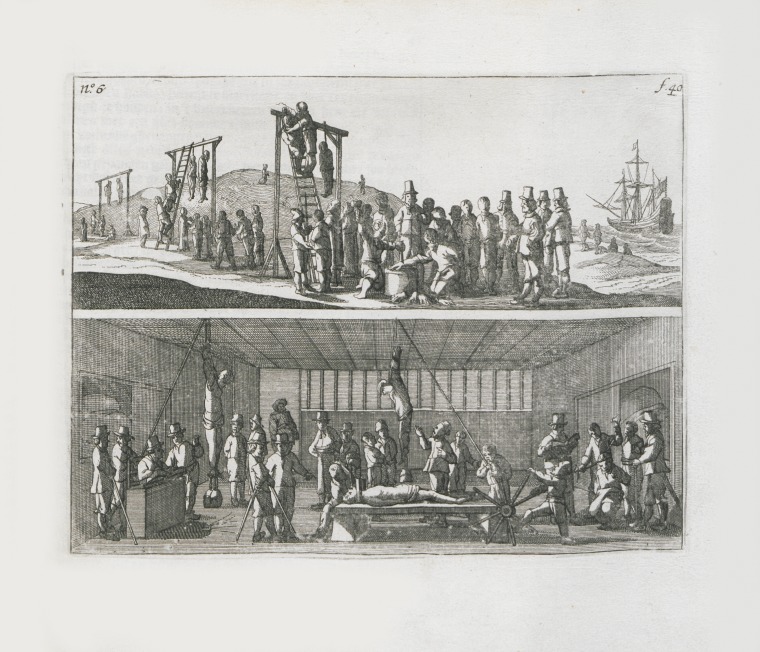

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_5

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

Ongeluckige voyagie, van 't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien

State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1660729_3

The Massacre Ends, but the Bloodshed Continues

Eventually, Cornelisz’s reign of terror came to an end. He and five of his men were overpowered and restrained by soldiers in a series of battles.

Soon after, help arrived in the form of the Sardam.

Pelsaert recorded in his journal:

‘Before noon, approaching the island, we saw smoke on a long island 2 miles West of the Wreck, also on another small island close by the Wreck, about which we were all very glad, hoping to find great numbers, or rather all people, alive. - Therefore, as soon as the anchor was dropped, I sailed with the boat to the highest island, which was nearest, taking with me a barrel of water, ditto bread, and a keg of wine; coming there, I saw no one, at which we wondered. I sprang ashore, and at the same time we saw a very small yawl with four Men rowing round the Northerly point; one of them, named Wiebbe Hayes, sprang ashore and ran towards me, calling from afar, ‘Welcome, but go back aboard immediately, for there is a party of scoundrels on the islands near the wreck, with two sloops, who have the intention to seize the Yacht.’

Hayes was able to explain to Pelsaert that he was holding Cornelisz prisoner. Pelsaert captured the remaining mutineers when they tried to board the Sardam:

‘When they came over, we immediately took them prisoner, and we forthwith began to examine them, especially a certain Jan Hendricxsz from Bremen , (49), soldier, who immediately confessed that he had murdered and helped to murder 17 to 20 people, under the order of Jeronimus [Cornelisz]. I asked him the origin and circumstances of this, why had they practiced such cruelties. Said the he also wished to explain how it had been with him in the beginning, - saying, that the skipper [Ariaen Jacobsz] Jeronimus Cornelisz, the Highboatswain [Jan Evertsz] and still more others, had it in mind to seize the ship Batavia before it was wrecked; to kill the Commandeur [Pelsaert] and all people except 120 towards whom they were more favourably inclined, and to throw the dead overboard into the sea and then to go pirating with the ship.’

After questioning Cornelisz, who would take no responsibility for his actions, Pelsaert set to the task of capturing the remaining mutineers. When they caught sight of him, the insurgents immediately surrendered.

The mutineers were interrogated and slowly Pelsaert pieced together the horror of what had happened, recording crimes including:

- Murder

- Rape

- Looting of VOC property

- Looting of private valuables

Following these various confessions, the condemned were sentenced to have their right hand cut off (and in the case of Cornelisz – both hands), before being executed in the gallows. These sentences were carried out on Seals Island on 2nd October 1629.

Instead of execution, two men were abandoned on the Southland as punishment, while it was decided that some less serious offenders would be taken back to Batavia (these people, after being flogged, keelhauled, and dropped from the yardarm on the voyage to Batavia, were promptly executed on arrival).

Later, Wiebbe Hayes and some of his men were rewarded with promotions. With the harrowing events of Batavia’s maiden voyage finally over, it was counted that only 116 out of the original 316 passengers had survived the shipwreck and mutiny (give or take several desertions, unrelated deaths, births, or other additional passengers).

The Discovery of the Batavia and her Graveyard

The Batavia was discovered 300 years after its wrecking and the tragic events that were to follow.

In 1963, successful excavations on Beacon Island revealed 17th Century Dutch artefacts in association with human remains, which led to the discovery of the wreck itself.

This discovery led to systematic archaeological research and recovery of parts of the ship and its cargo, as well as analysis of artefacts and human remains found on Beacon Island (Batavia’s Graveyard).

The Batavia herself was excavated in four seasons of fieldwork commencing in 1972 and was one of the first excavations undertaken by the WA Museum’s Department of Maritime Archaeology.

Please note: This story has been re-written for brevity. Read the original on the WA Museum website - museum.wa.gov.au/maritime-archaeology-db/roaring-40s/batavia

Silver bowl from the Batavia shipwreck

Silver bowl from the Batavia shipwreck

Western Australian Museum – BAT03009-002

Taler or Rijksdaalder from the Batavia shipwreck

Taler or Rijksdaalder from the Batavia shipwreck

Western Australian Museum – 01582-C.

Taler from the Batavia shipwreck

Taler from the Batavia shipwreck

Western Australian Museum – 00839-C

Stoneware from the Batavia shipwreck

Stoneware from the Batavia shipwreck

Western Australian Museum – BAT00539-003

Corroded key from Batavia shipwreck

Corroded key from Batavia shipwreck

Western Australian Museum – BAT00344-001

Armament from the Batavia shipwreck

Armament from the Batavia shipwreck

State Library of Western Australia – BAT80579-001