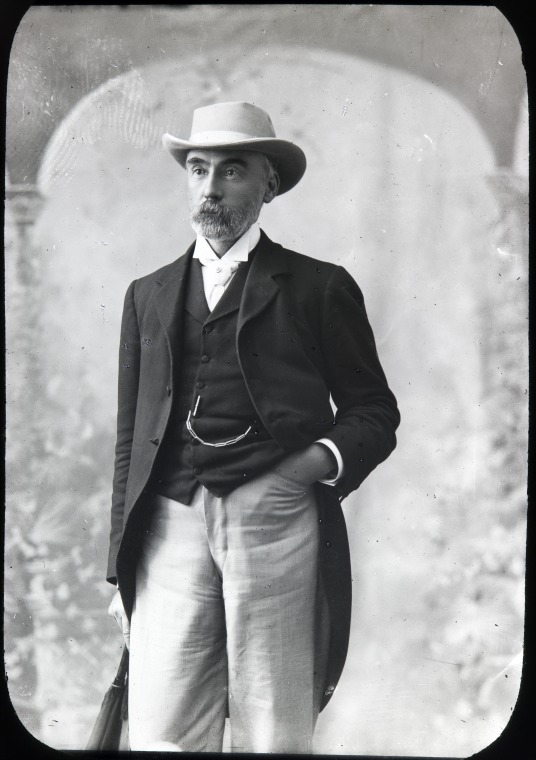

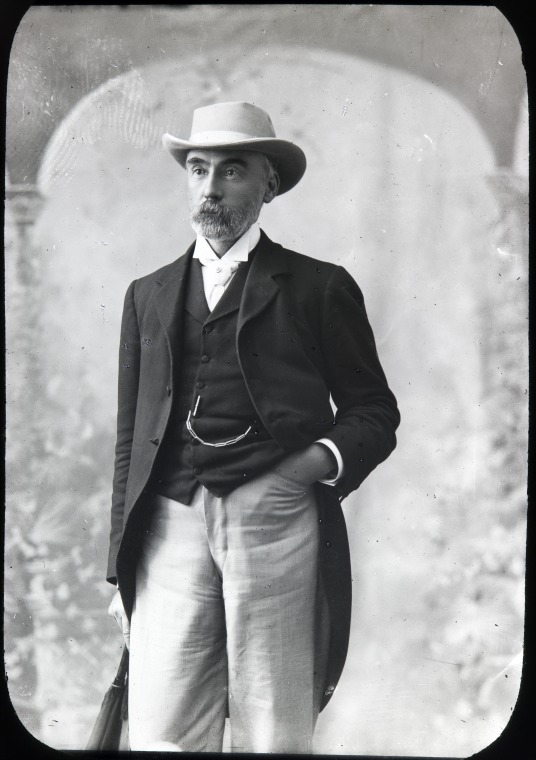

Charles Yelverton O’Connor CMG (11 January 1843 – 10 March 1902) was the first Engineer-in-Chief of Western Australia.

Recruited by Sir John Forrest, the Premier of Western Australia at the time, he was tasked with improving the colony's railways, roads, water supply, and harbours.

His two most notable projects included the development of Fremantle Harbour and the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme.

C.Y. O'Connor [picture]1 lantern slide : glass, b&w ; 8 x 8 cm.State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2103153_1

C.Y. O'Connor [picture]1 lantern slide : glass, b&w ; 8 x 8 cm.State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2103153_1Early Life and Arrival in WA

O'Connor was born on 11 January 1843 at ‘Gravelmount’, Castletown, near Navan, County Meath, Ireland.

At 17 he began training to become a civil engineer, and he quickly gained experience working on railway construction and water-control projects. In 1865 O'Connor migrated to New Zealand to begin his career in this field.

During his time in New Zealand he worked on projects that involved supplying water to goldmines, improving harbour facilities, and constructing railway tracks, roads, and bridges. This work gained him an international reputation, and led to his election to the Institution of Civil Engineers, London in 1880.

In April 1891, Sir John Forrest, premier of Western Australia, offered O'Connor the position of Engineer-in-Chief working for the Public Works Department. When O'Connor asked whether his responsibilities would cover railways, harbours or roads, Forrest replied with "Everything".

O'Connor, with his wife Susan Laetitia Ness (married March 1874) and their seven children (four girls and three boys) migrated to Western Australia that same year.

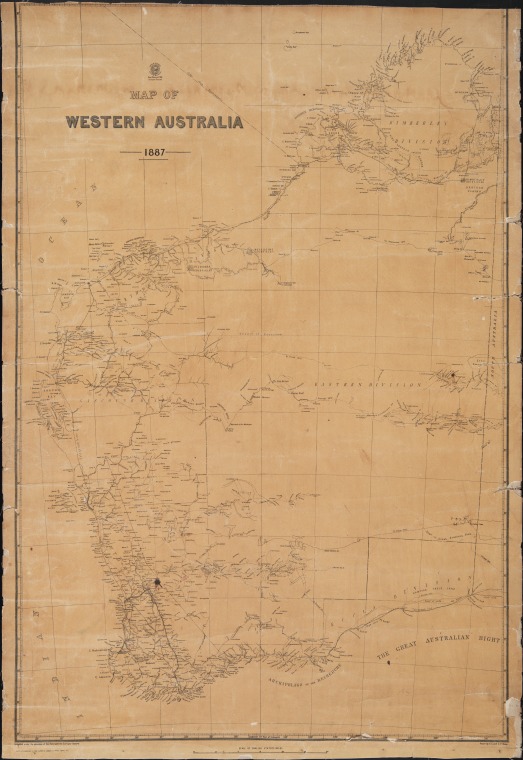

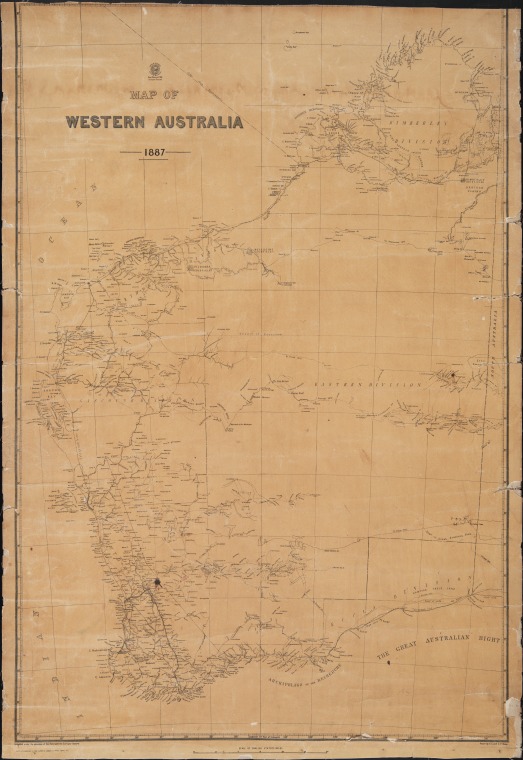

Map of Western Australia 1887State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2140531_2

Map of Western Australia 1887State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2140531_2 C.Y. O'Connor and family, Wellington, New Zealand (1891)Left to right: Standing - Eva, George, Aileen, Kathleen. Sitting - Roderick, Mrs O'Connor, Murtagh, Charles Yelverton and Bridget.State Library of Western Australia – BA521/5

C.Y. O'Connor and family, Wellington, New Zealand (1891)Left to right: Standing - Eva, George, Aileen, Kathleen. Sitting - Roderick, Mrs O'Connor, Murtagh, Charles Yelverton and Bridget.State Library of Western Australia – BA521/5

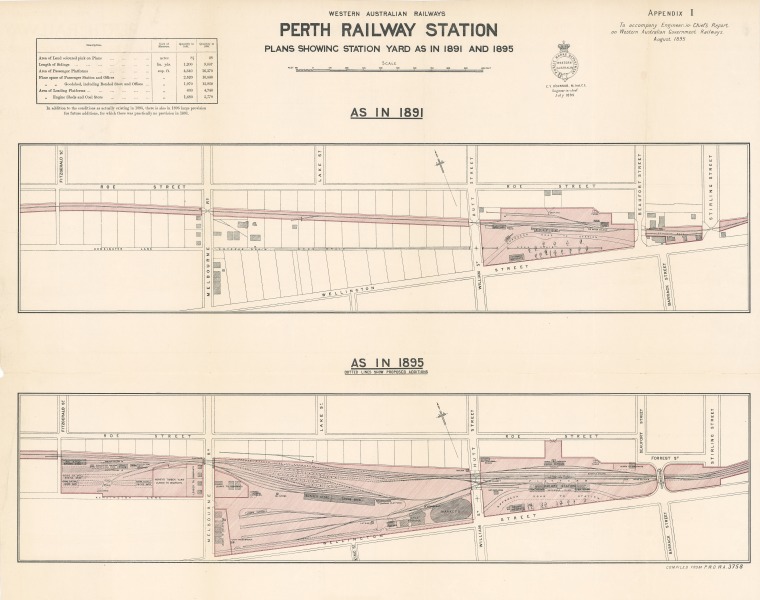

Improving the Railways

In addition to being Engineer-in-Chief O'Connor was also the General Manager of Railways.

During his time in this position O'Connor faced much opposition and criticism on the basis of limited funding. Despite this, O'Connor's vigorous research meant he was able to succeed in actioning many of his plans that sought to improve the colony.

His work saw Western Australia's railway system vastly increased, with lines extending as far as Northam, Coolgardie, and Kalgoorlie.

Conditions in the cramped and ill-equipped maintenance and repair workshops were also immediately improved, although his attempts to upgrade and relocate the workshops in Fremantle took 12 years to receive funding.

O'Connor also advanced the wellbeing of Western Australia's railway workers as he vocalised their abhorrent working conditions. This eventuated in better conditions and educational opportunities for these workers.

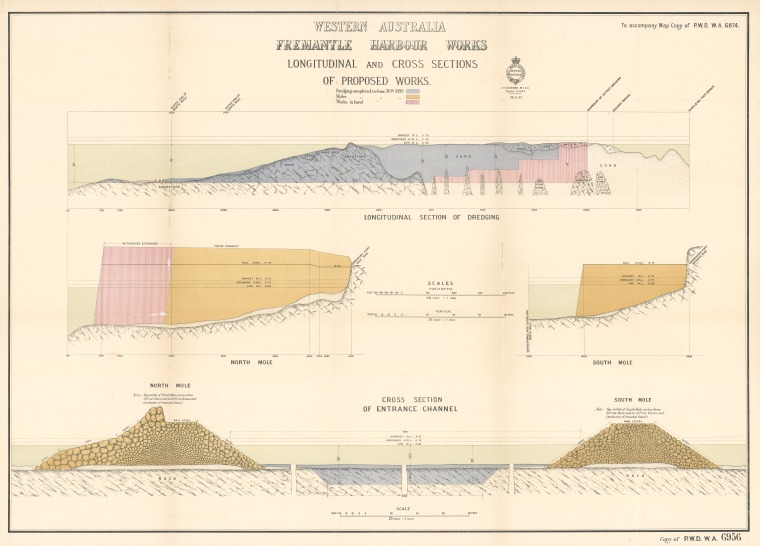

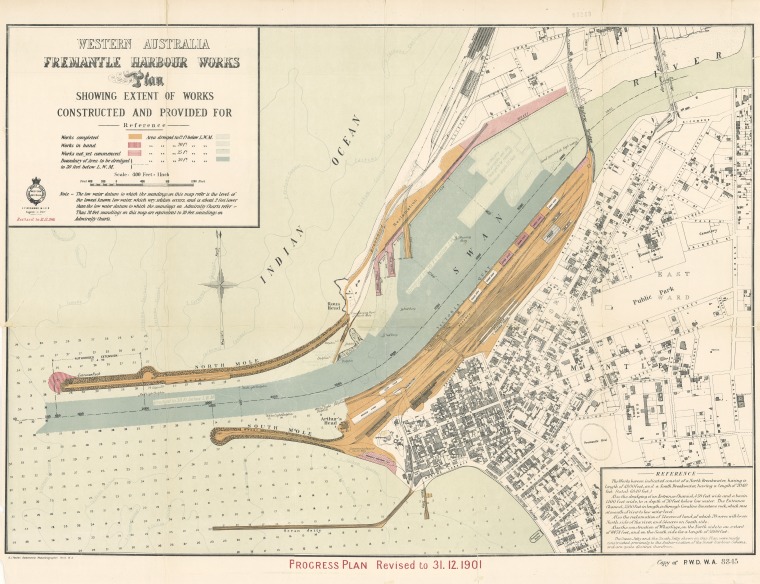

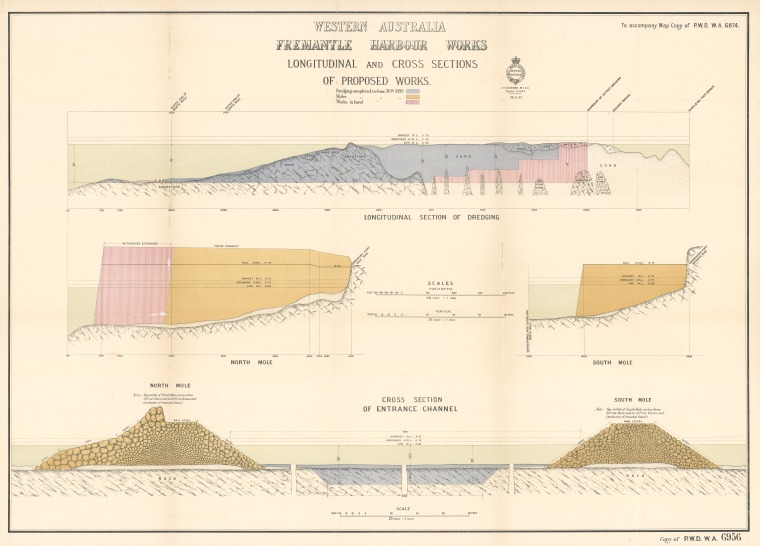

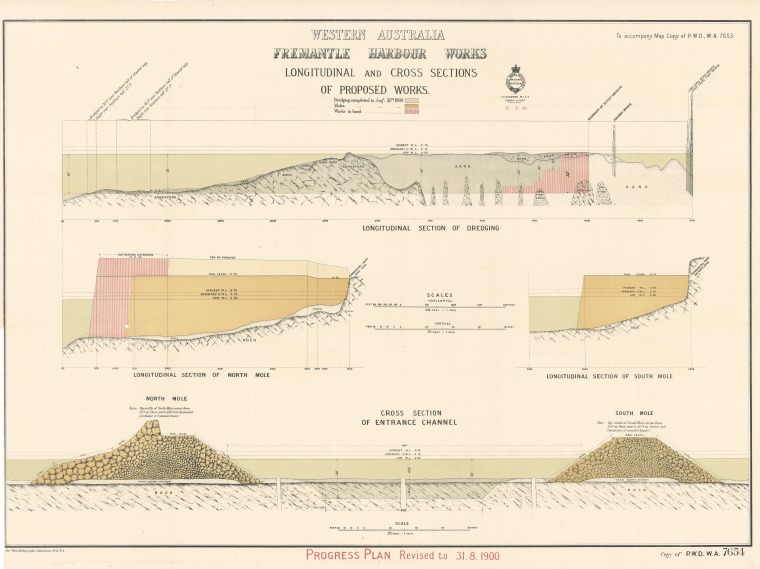

Fremantle Harbour

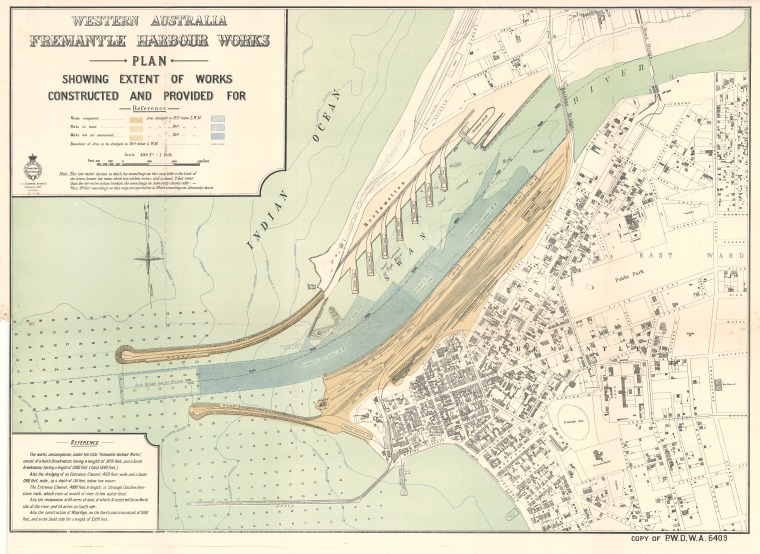

The first project on Forrest’s program of public works was the development of a modern harbour to be established in Fremantle. The harbour needed to accommodate the royal mail contractors whose vessels were the largest steamers entering Australia.

The entrance to the Swan River, which had been outlined as the harbour site, was obstructed by a large limestone bar. Original plans created in 1887 by Sir John Coode addressed this issue by proposing the construction of an outer harbour.

When supplied with Coode's plans, O'Connor doubted whether it was the best solution. After extensive research, O'Connor proposed the removal of the limestone bar with explosives and further clearing through dredging. By doing this, O'Connor demonstrated that an extensive sheltered harbour with opportunity for future extension could be built.

O'Connor's harbour was officially opened in 1897 by Lady Forrest, and in 1900 the mail station was altered from Albany to Fremantle. The success of the harbour was evident to all when on 12 September the R.M.S. Himalaya, carrying mail from London, entered the inner harbour and berthed.

For his work on Fremantle Harbour O'Connor was invited to London where he was inducted as a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG).

According to Nyoongar creation time, the mouth of the Derbal Yerrigan (Swan River) is the place where the Wagyl (a serpent creation being) fought a Crocodile Spirit and used the crocodile’s tail to separate the fresh water from salt water.

This ‘tail’ was the rocky limestone bar that stretched across the mouth of the Swan River to form the estuary. Being shallow it was a good crossing point for Aboriginal men. After the bar of rock was removed by O'Connor in accordance with the Harbour plans, only a small part of the tail remains.

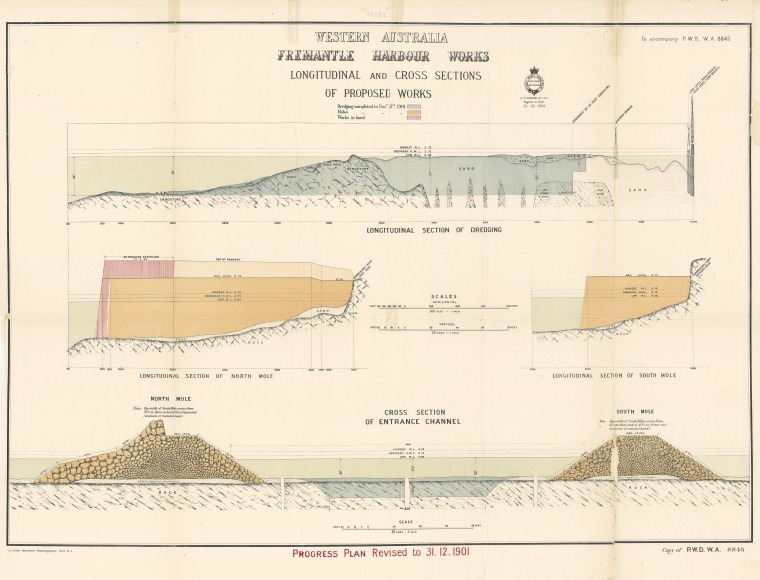

Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1899)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2177961_2

Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1899)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2177961_2 Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1900)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2810525_2

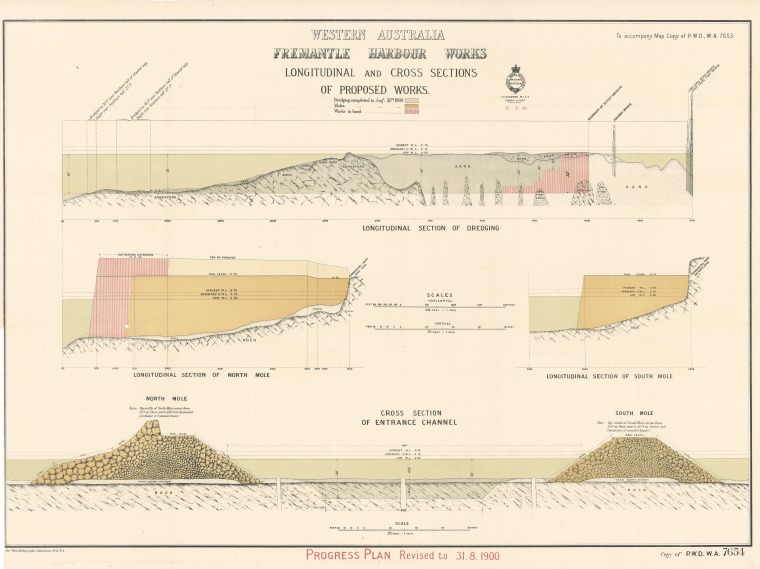

Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1900)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2810525_2 Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2230201_2

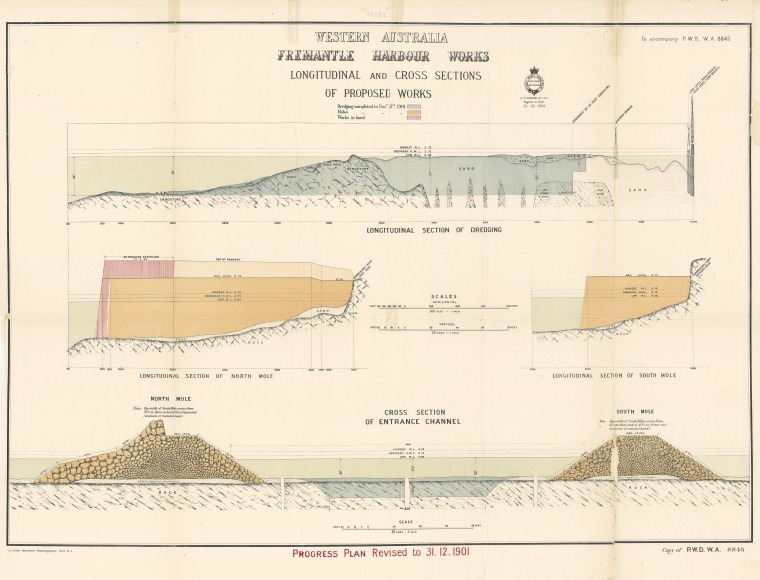

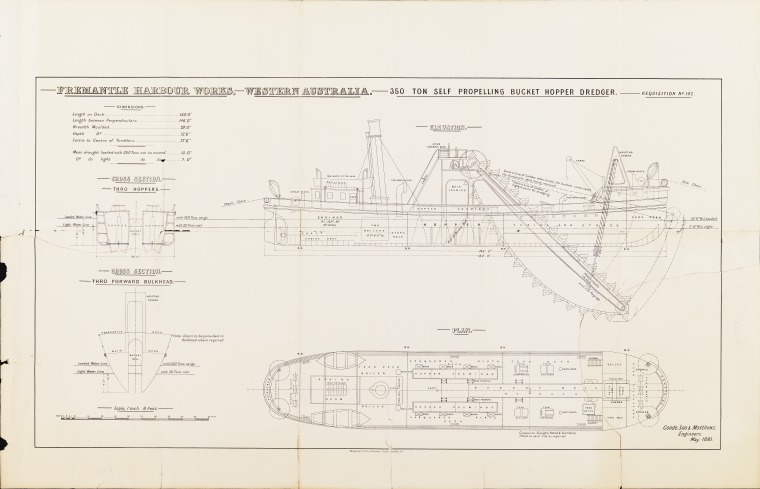

Fremantle Harbour works longitudinal and cross sections of proposed works (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2230201_2 Fremantle Harbour works, dredger detailsState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1924377_1

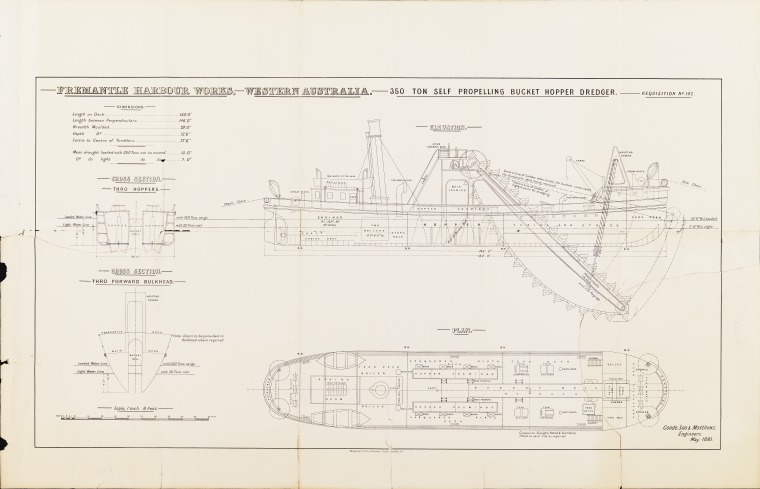

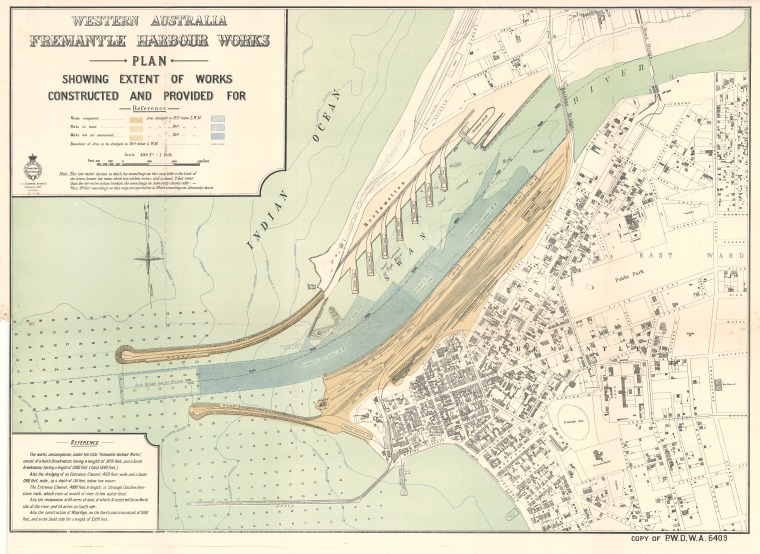

Fremantle Harbour works, dredger detailsState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1924377_1 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1898)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2177940_2

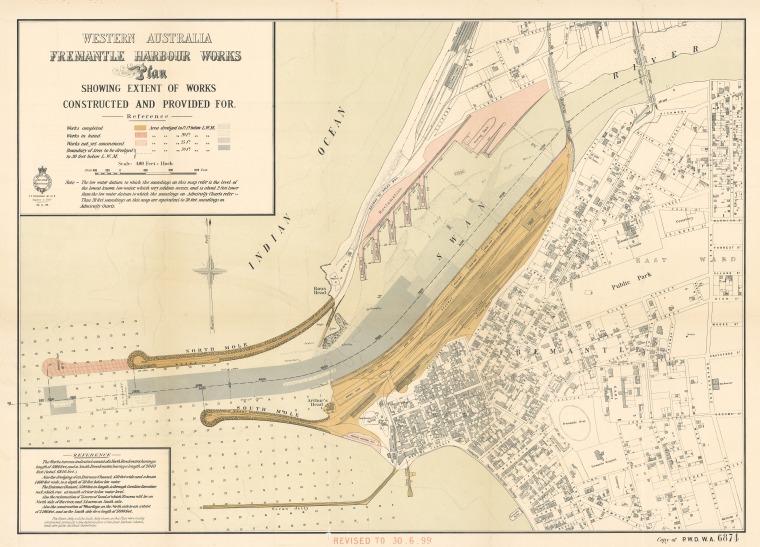

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1898)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2177940_2 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811085_2

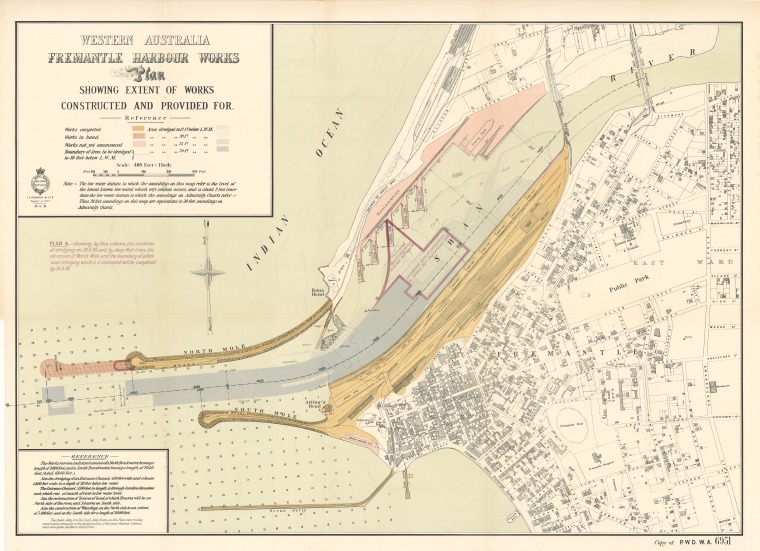

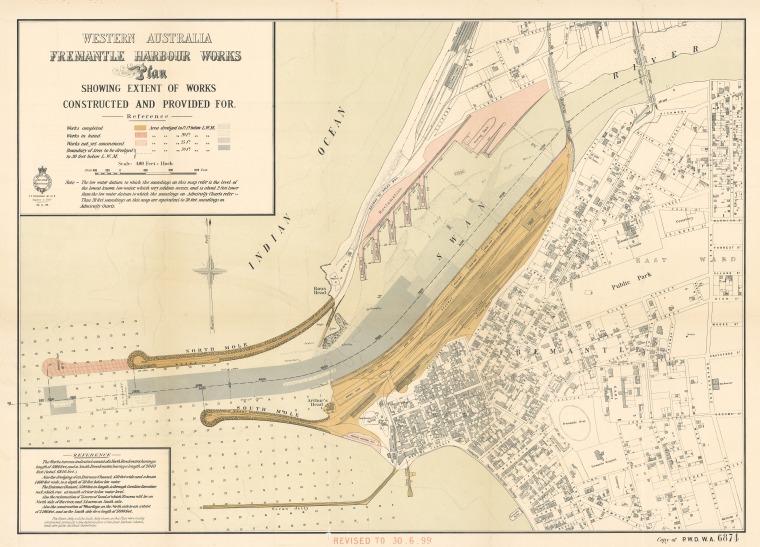

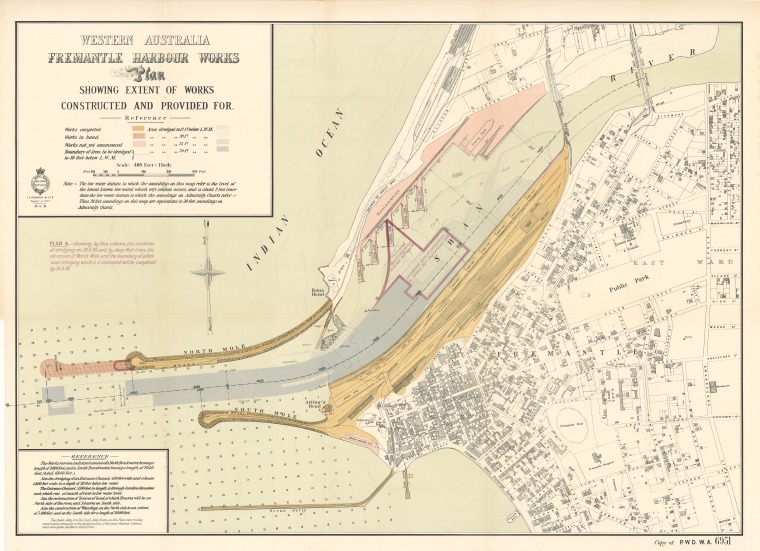

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811085_2 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899A)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811086_3

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899A)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811086_3 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899B)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811086_4

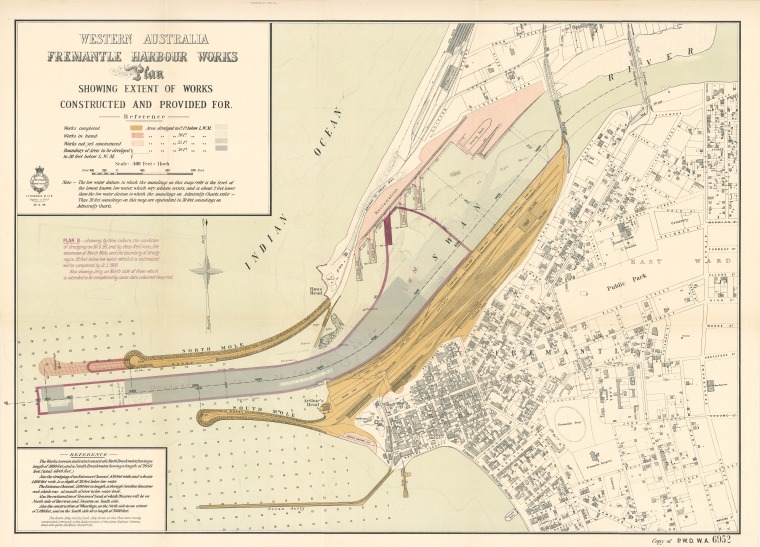

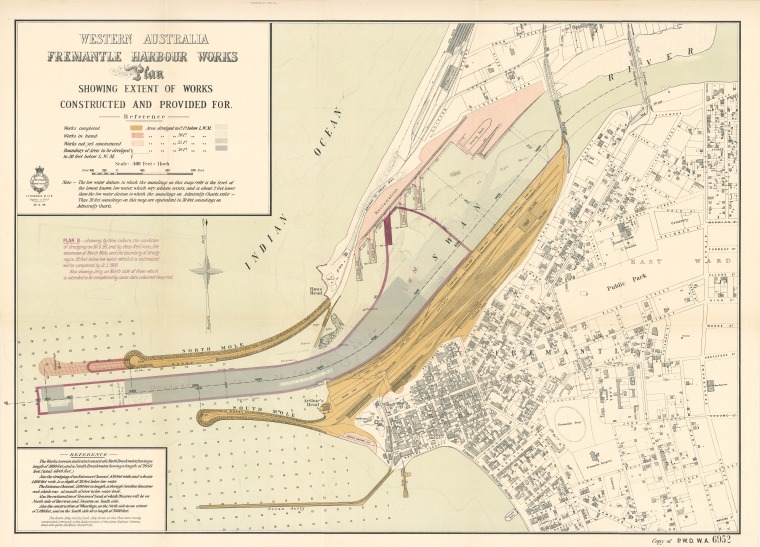

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1899B)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811086_4 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1900)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811087_2

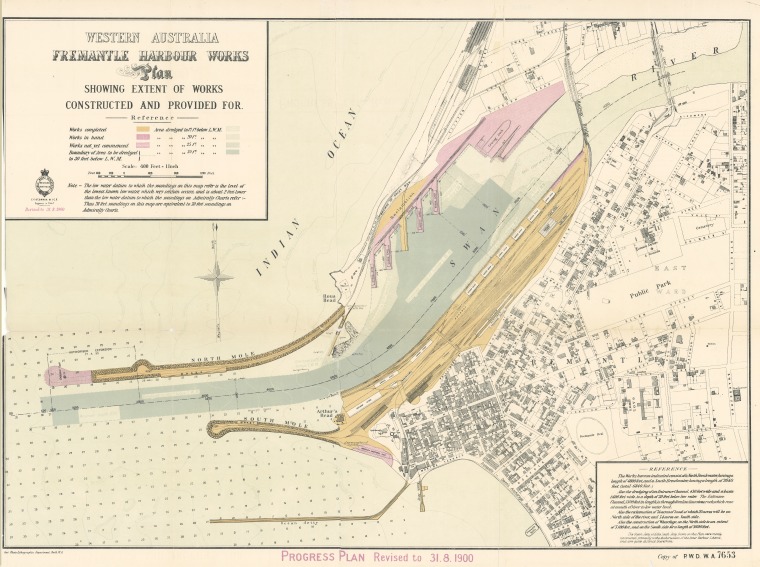

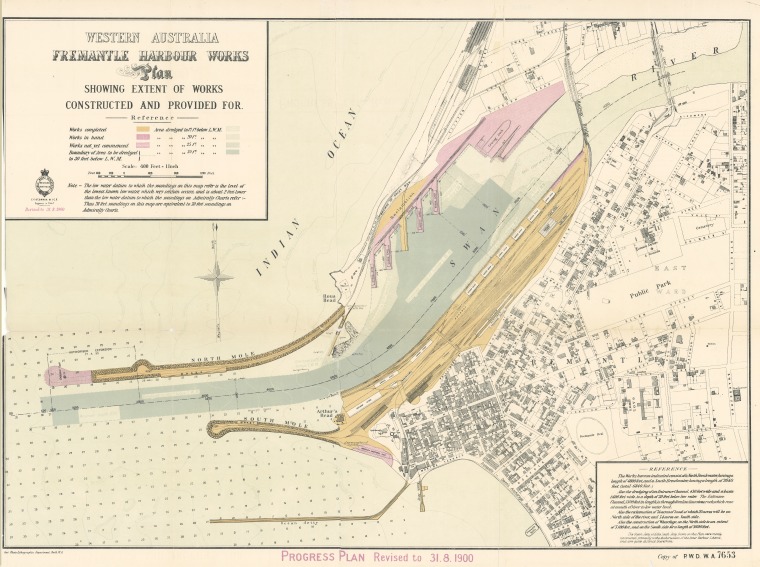

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1900)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811087_2 Fremantle Harbour works plan (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811088_2

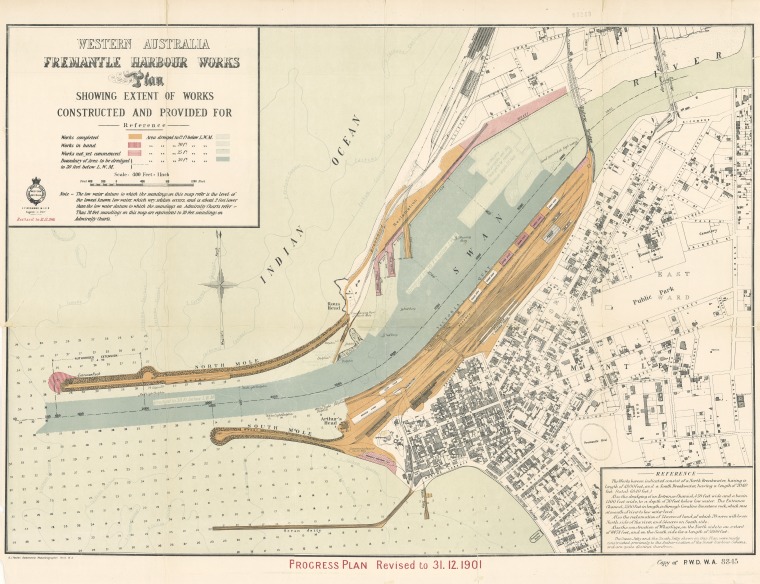

Fremantle Harbour works plan (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2811088_2 Panorama of Fremantle Harbour (1905)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1967359_1

Panorama of Fremantle Harbour (1905)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b1967359_1

Goldfields Water Supply Scheme

The gold discoveries in Western Australia in the 1890s attracted thousands of miners, immigrants, and new settlers. This population boom meant that by the mid-1890s over 40% of WA's population lived on the Eastern Goldfields.

Lack of rainfall and an absence of large quantities of fresh water meant that these communities were left to live in inadequate and unsanitary living conditions. Between 1896-1898, the Goldfields had a death rate of 16 per thousand, largely due to the prevalence of typhoid fever.

In 1895 O’Connor completed details of a plan to construct a 560km pipeline that would pump water from Mundaring to the Goldfields. The pipeline would be capable to supply these communities with more than 20 million litres of water each day.

The magnitude of this project led to significant opposition and criticism in Parliament regarding its practicality. The cost of constructing the pipeline would be equal to the colony's entire annual budget. After much debate and delay the scheme was finally granted funding and permission in 1898.

Work on the pipeline was successfully completed in January 1903 and Lady Forrest 'started' the pumping machinery at an official ceremony on 22 January of that year.

The pipeline is still in use today, and regularly maintained.

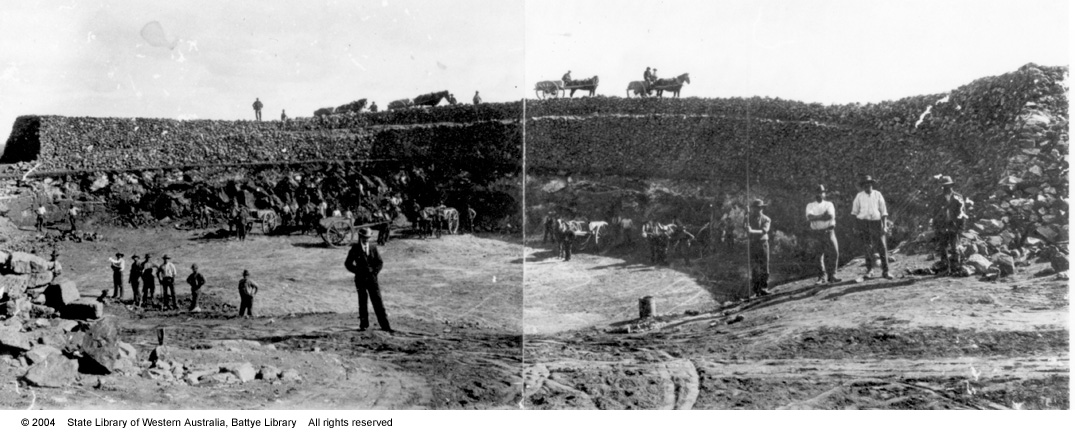

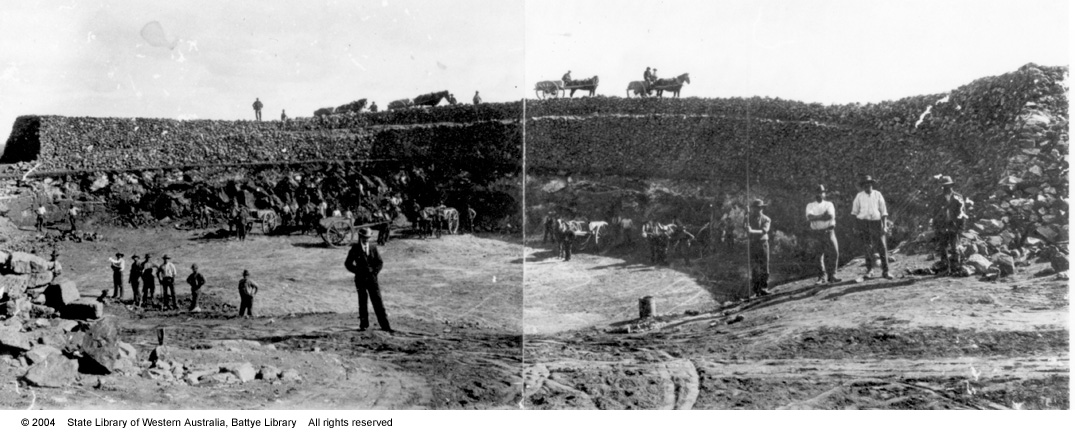

Construction of Mt Charlotte Reservoir, Kalgoorlie (1898)State Library of Western Australia – 3358B/29

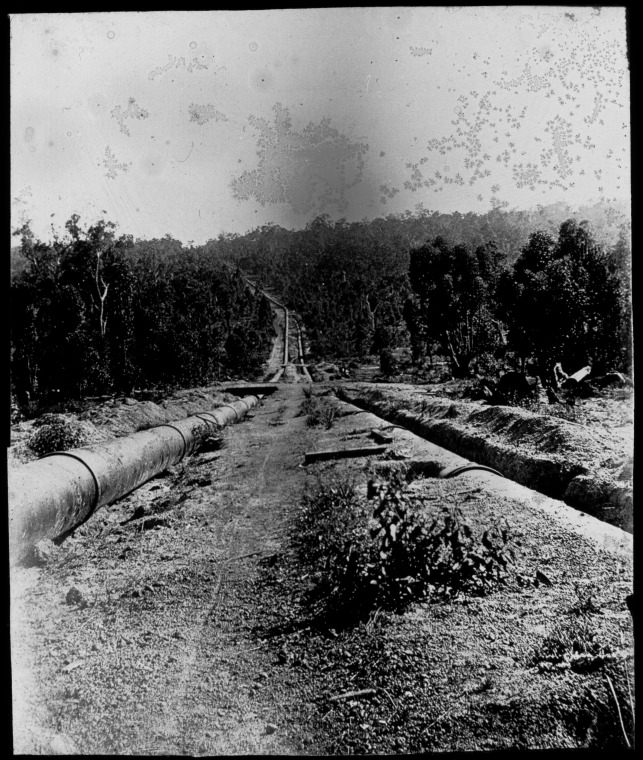

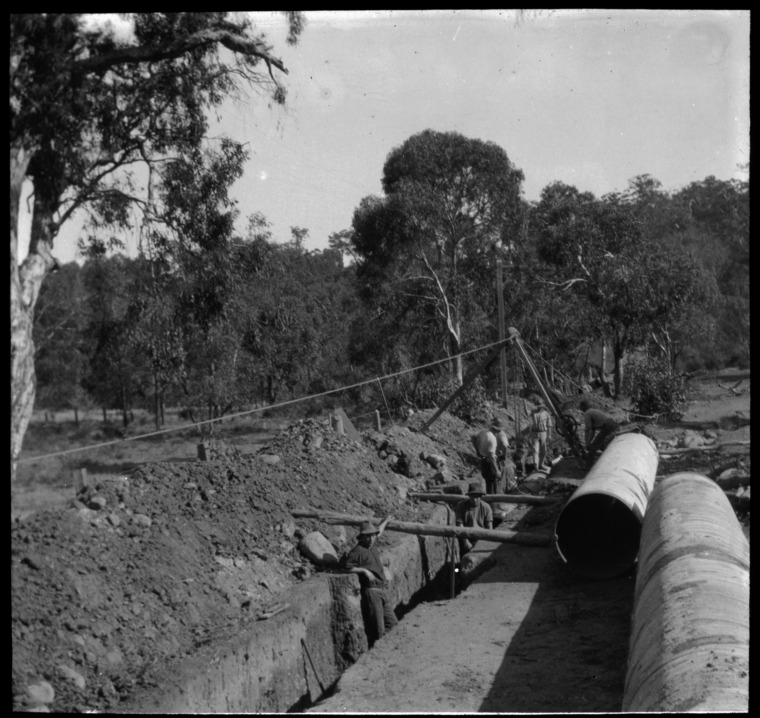

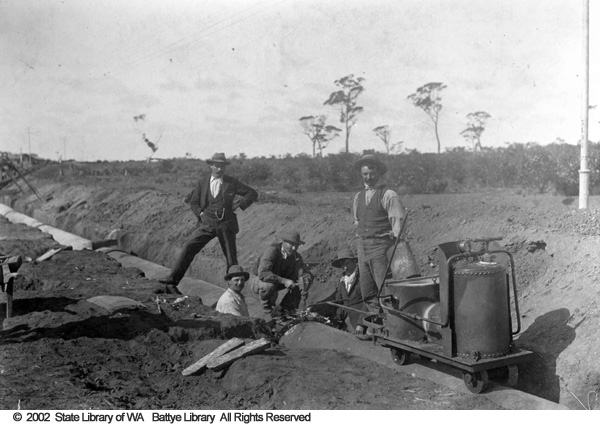

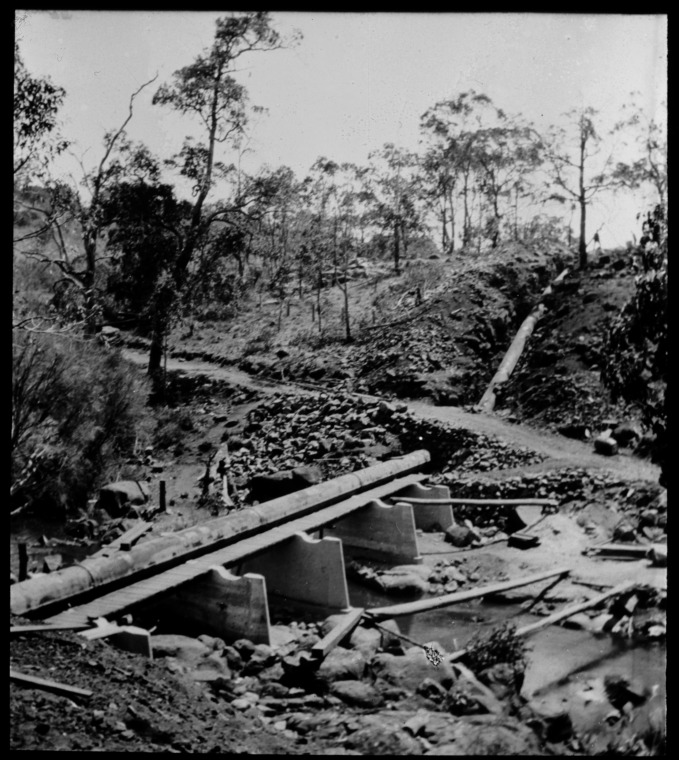

Construction of Mt Charlotte Reservoir, Kalgoorlie (1898)State Library of Western Australia – 3358B/29 Laying pipes across Darling Ranges (1902)State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/27

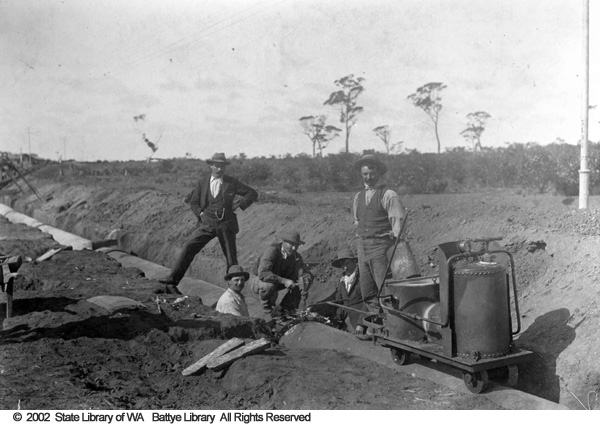

Laying pipes across Darling Ranges (1902)State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/27 Caulking machine for lead joints in the Goldfields Water Pipeline (1901) [2 images]State Library of Western Australia – 3359B/15-16

Caulking machine for lead joints in the Goldfields Water Pipeline (1901) [2 images]State Library of Western Australia – 3359B/15-16 Caulking machine for lead joints in the Goldfields Water Pipeline (1901) [2 images]State Library of Western Australia – 3359B/15-16

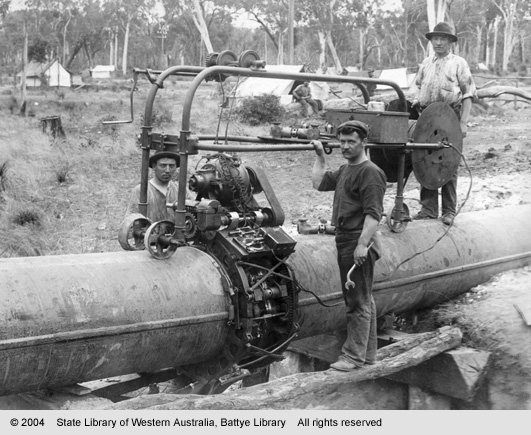

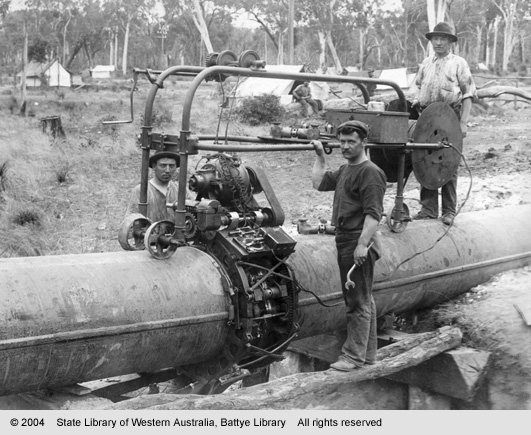

Caulking machine for lead joints in the Goldfields Water Pipeline (1901) [2 images]State Library of Western Australia – 3359B/15-16 Electric caulking machine on the Goldfields Water Scheme pipeline (1902) [4 images]State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/17-20

Electric caulking machine on the Goldfields Water Scheme pipeline (1902) [4 images]State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/17-20 Electric caulking machine on the Goldfields Water Scheme pipeline (1902) [4 images]State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/17-20

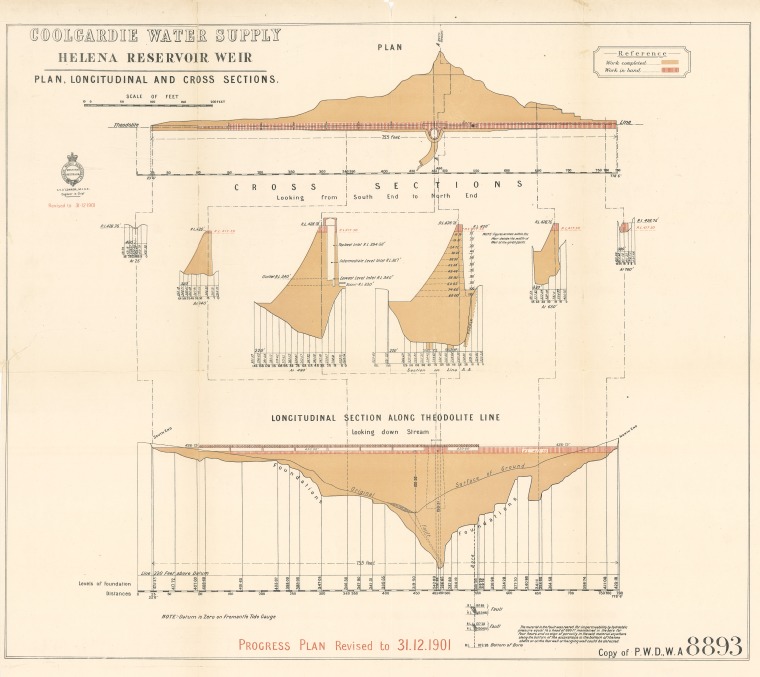

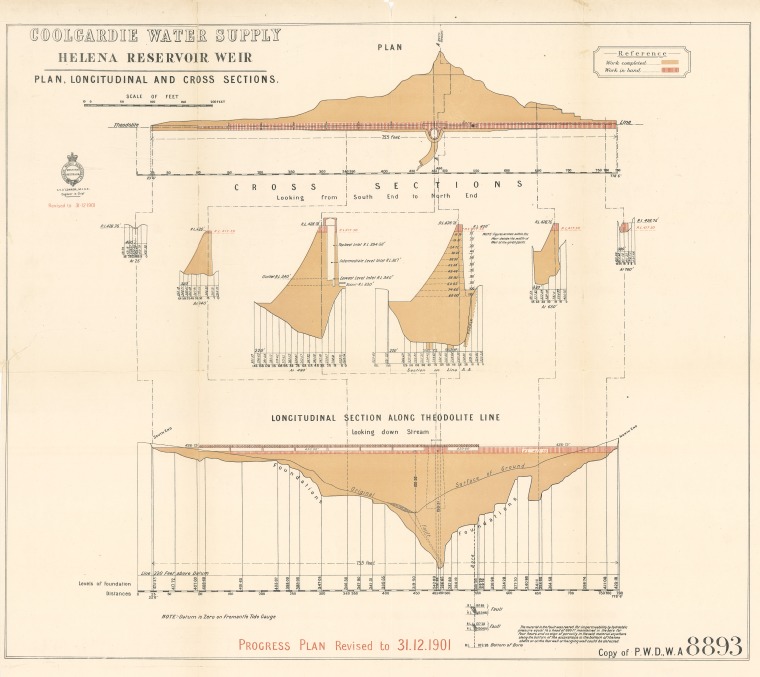

Electric caulking machine on the Goldfields Water Scheme pipeline (1902) [4 images]State Library of Western Australia – BA1471/17-20 Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal and cross sectionsState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2819681_2

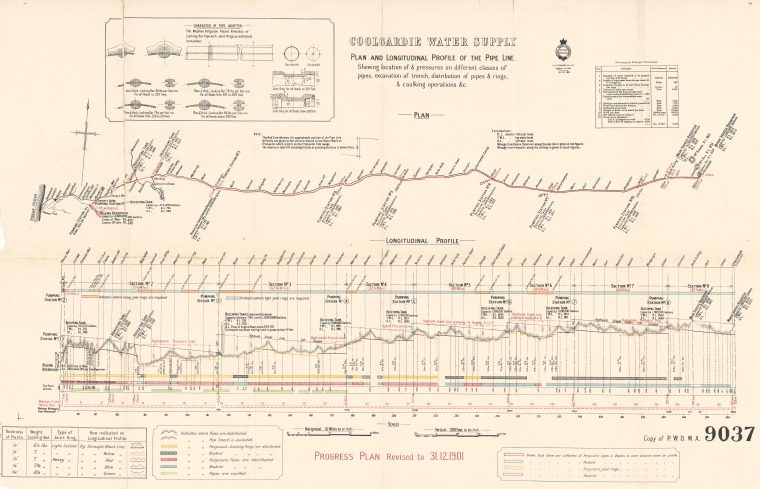

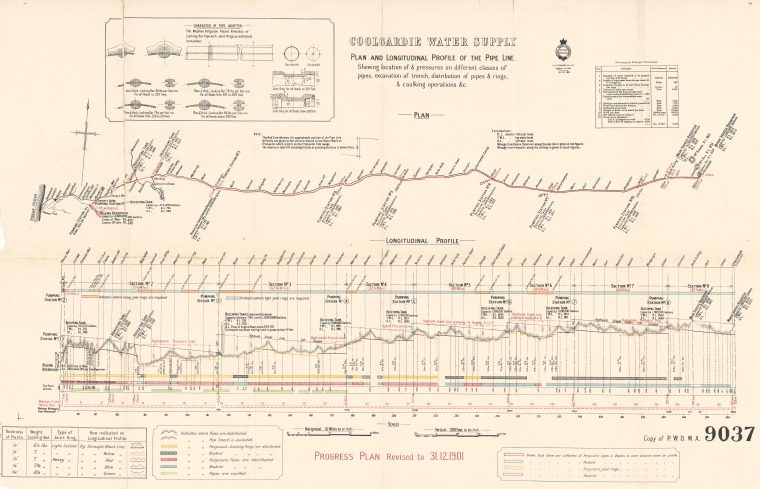

Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal and cross sectionsState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2819681_2 Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal profile of the pipeline (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2817838_2

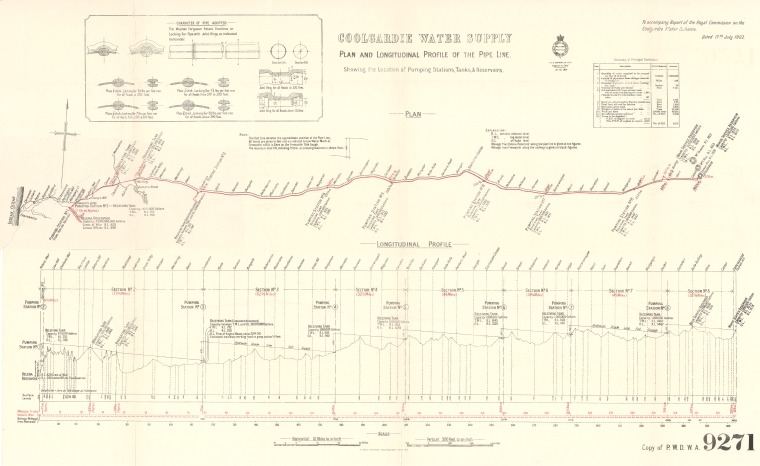

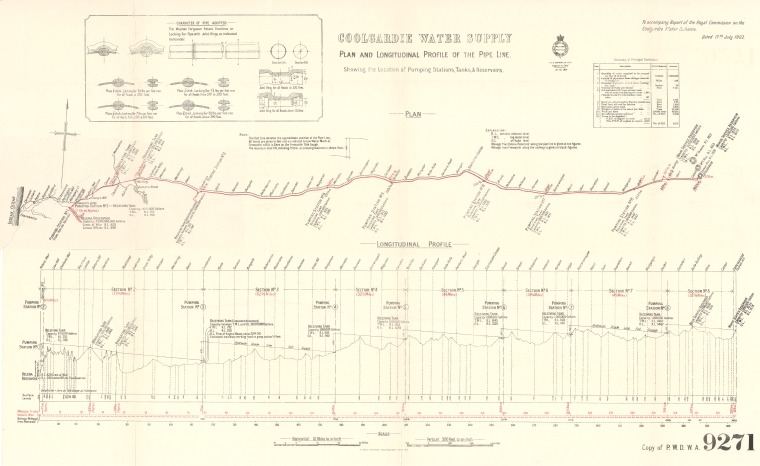

Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal profile of the pipeline (1901)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2817838_2 Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal profile of the pipeline (1902)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2817839_2

Coolgardie water supply plan, longitudinal profile of the pipeline (1902)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b2817839_2 Mundaring Weir and the O'Connor Museum, formerly No. 1 pumping station, January 1993State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3005381_4

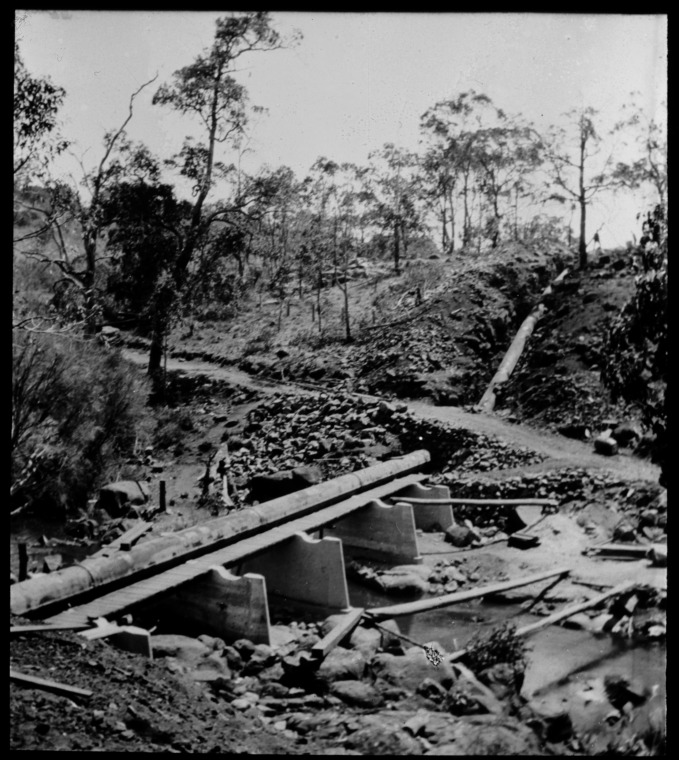

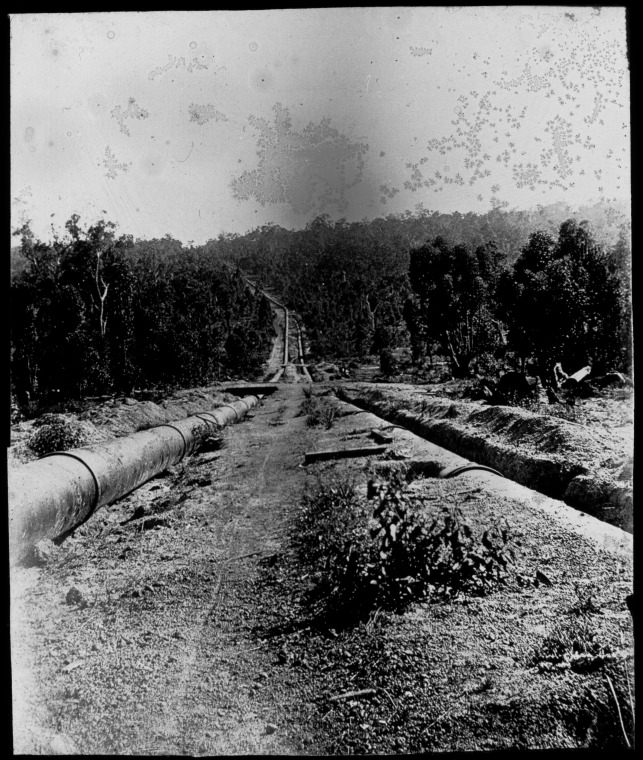

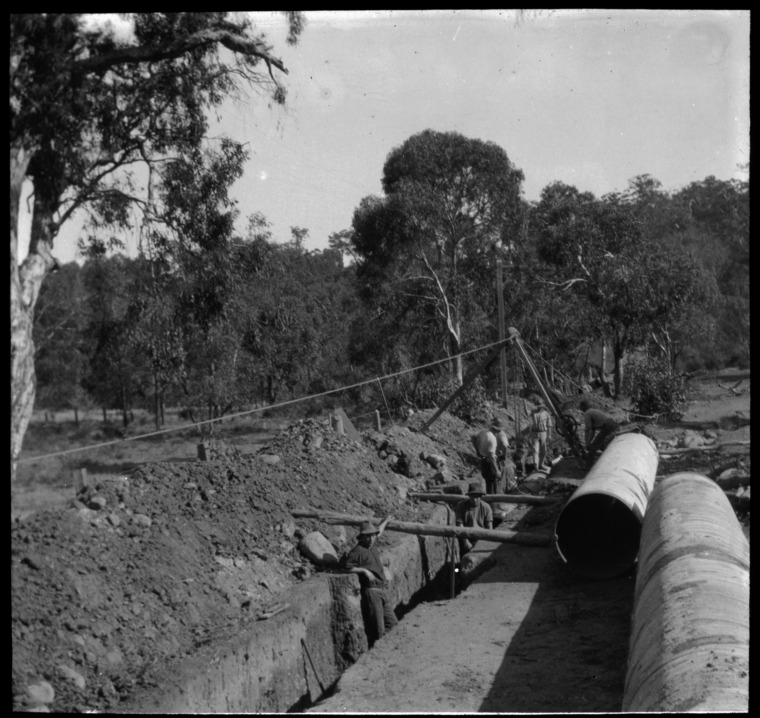

Mundaring Weir and the O'Connor Museum, formerly No. 1 pumping station, January 1993State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3005381_4 Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_6

Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_6 Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_8

Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_8 Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_10

Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_10 Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_2

Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_2 Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_3

Construction, transport, installation, and views of the Goldfields Water Supply pipelineState Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3755959_3 The Goldfields Pipeline near Kellerberrin (1961)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3987966_1

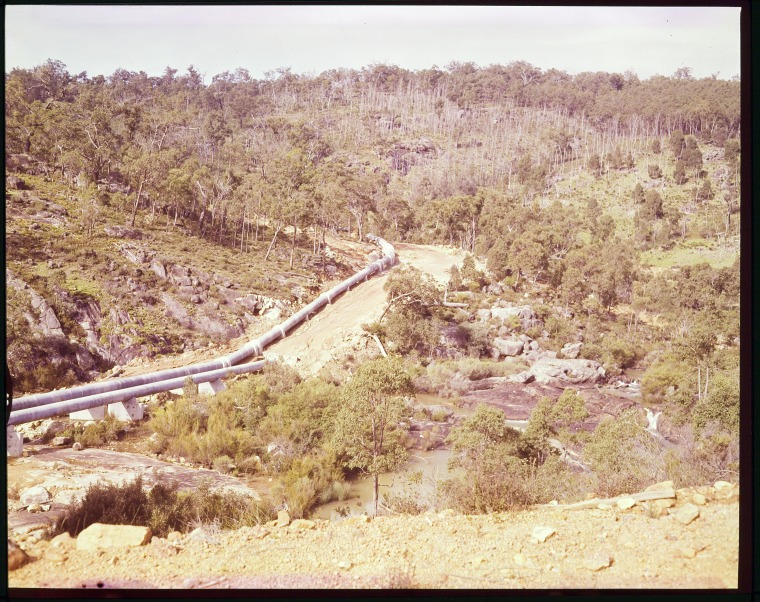

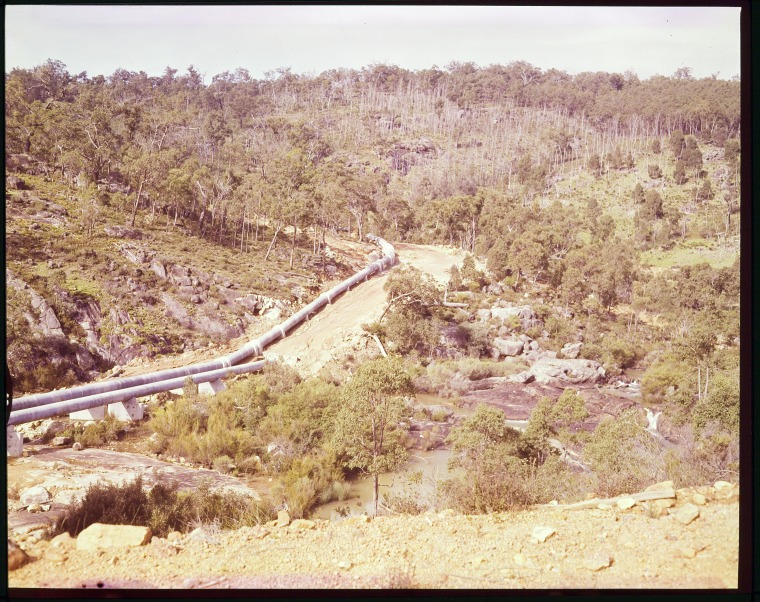

The Goldfields Pipeline near Kellerberrin (1961)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3987966_1 Goldfields pipeline, possibly near Mundaring Weir (1962)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3760386_1

Goldfields pipeline, possibly near Mundaring Weir (1962)State Library of Western Australia – slwa_b3760386_1

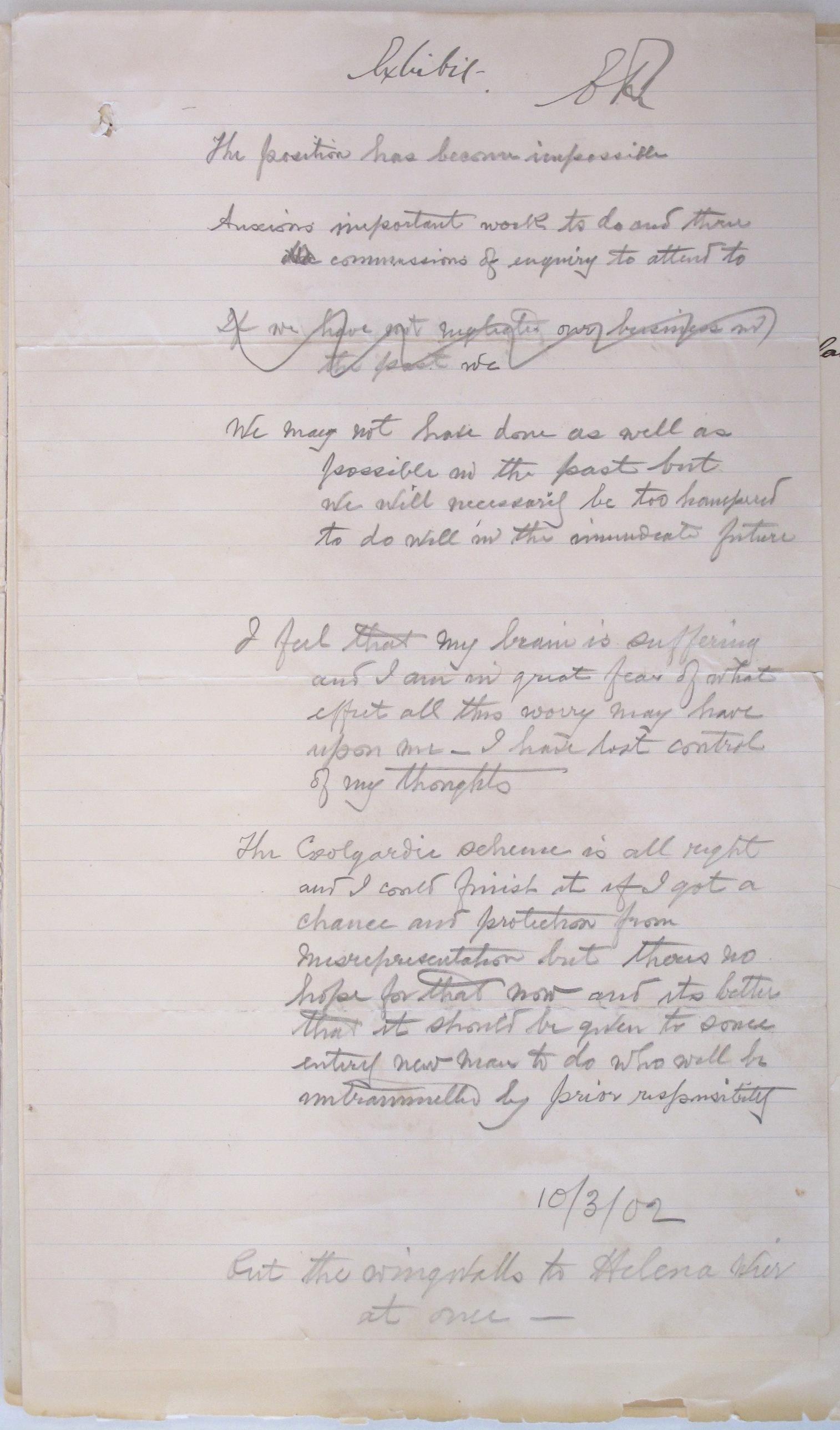

Death

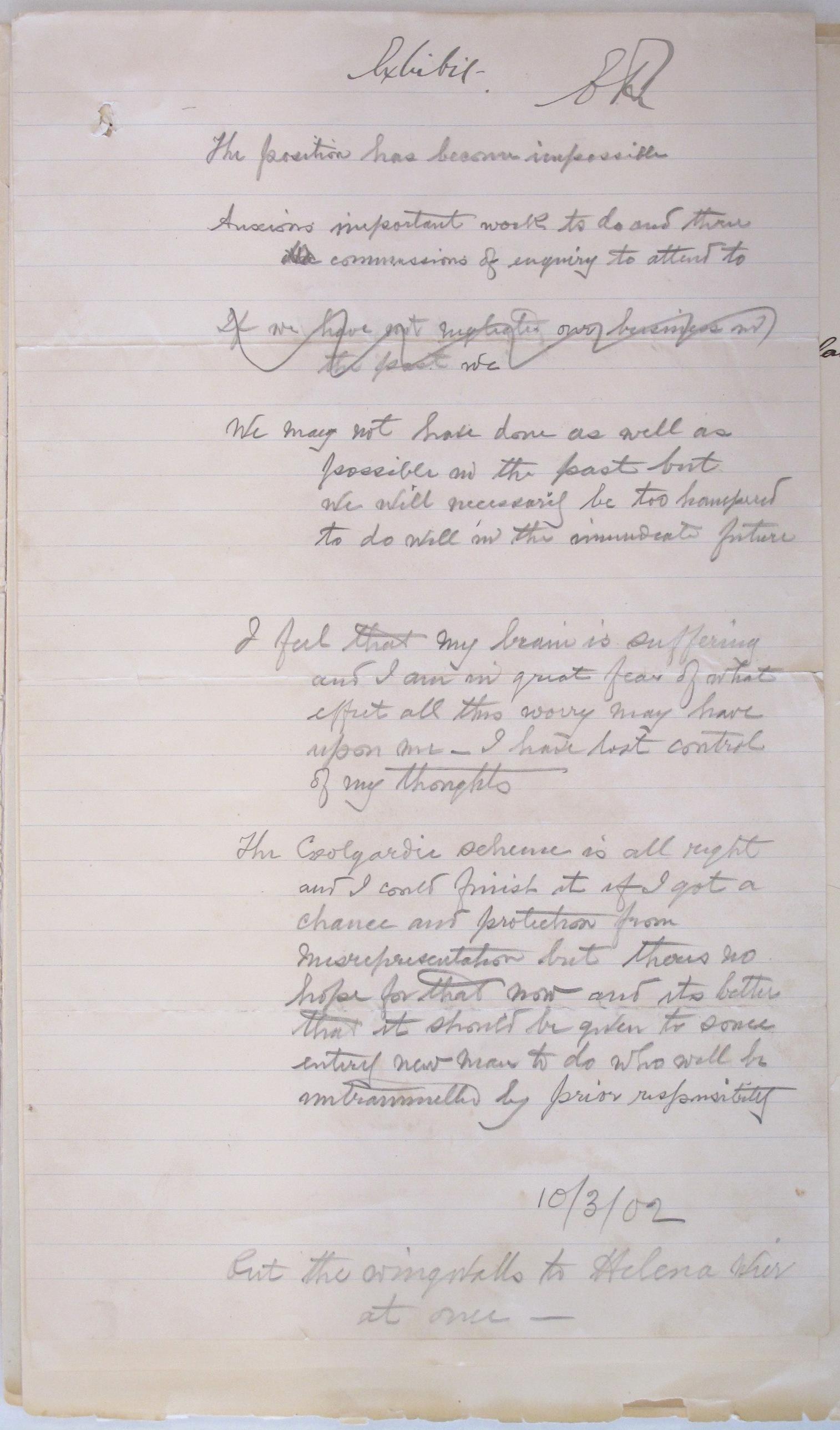

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme received a significant amount of unwarranted criticism—particularly from the media.

The unrelenting criticism, delays, and the lack of funding and co-operation took its toll on O'Connor who chose to take his own life on 10 March 1902.

That morning he took his customary early morning horse ride past Fremantle Harbour, then south to Robb Jetty. Once there he rode his horse into the sea and shot himself.

O'Connor unfortunately did not live to see the successful completion of his Goldfields Water Supply Scheme.

CY O'Connor's dying declaration and Coroner's Inquest file 1902/20 with the post-mortem and Coroner's reportState Records Office of WA – AU WA S2664- cons997 1902/0976

CY O'Connor's dying declaration and Coroner's Inquest file 1902/20 with the post-mortem and Coroner's reportState Records Office of WA – AU WA S2664- cons997 1902/0976

Character and Project Legacy

O’Connor found his recreation in horse riding, was reputedly a delightful host and was patron of several sports club in Fremantle. He was known as a compassionate man with an innate sense of justice.

Pride in his work and devotion to his family characterised the man who achieved brilliant civil engineering feats and was, according to his private secretary, 'a genius’ and a man of ‘extraordinary foresight’.

O’Connor’s two most notable engineering projects in WA are commemorated with statues. One in Fremantle, looking out over the harbour he created, and a bust at Mundaring Weir, commemorating a key part of the pipeline project.

In 2009, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the Goldfields pipeline an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

At the time of its opening the project was the largest engineering undertaking of its time. The amount of steel used in construction was greater than any steel structure elsewhere in the world, and never before had water been pumped so far or lifted so high.

The Goldfields pipeline is also listed on the National Heritage List as it continues to generate billions of dollars in economic activity. Despite a decline in the production of gold, the regular supply of water to the Goldfields meant that agriculture was able to prosper.

Today Western Australia's wheat fields are the most productive in Australia, accounting for 42% of the nation's wheat crop. In addition to this six million sheep rely on the water that the pipeline carries.

Office SafeUsed by C.Y. O'Connor, first Engineer-in-Chief who was in the office from 1891-1902.Western Australian Museum – CH1970.108

Office SafeUsed by C.Y. O'Connor, first Engineer-in-Chief who was in the office from 1891-1902.Western Australian Museum – CH1970.108 Desk paper traysUsed by C.Y. O'ConnorWestern Australian Museum – CH1970.863

Desk paper traysUsed by C.Y. O'ConnorWestern Australian Museum – CH1970.863 Ruler & French Curves - CY O'ConnorUsed by C.Y. O'ConnorWestern Australian Museum – T1970.963.a-k

Ruler & French Curves - CY O'ConnorUsed by C.Y. O'ConnorWestern Australian Museum – T1970.963.a-k